030 | The Magnetic Fields | 69 Love Songs [Merge, 1999]

[Merge, 1999]

In the years following the release of Stephen Merritt’s magnum opus, its legend grew. Once I got my copy, the set’s three discs didn’t leave rotation in my car for months. Every road trip became an excuse to listen to the set from start to finish, the same way my parents listen to musicals every time they hit the road. And that comparison makes sense—Merritt’s songs are elegant and rich, its melodies ranging from gorgeous to playful, and its range of styles is breathtaking, from the retro bubblegum of easy standout and mixtape fave “The Luckiest Guy on the Lower East Side,” to the gorgeous and sublimely sentimental “Nothing Matters When We’re Dancing,” to the playfully twee “Queen of the Savages,” to the willfully obtuse flash-gag of “Experimental Music Love.” Across the album’s sixty-nine songs, Merritt’s vision—both melodic and lyrical—is unimpeachable, as his obsessive approach to exploring love in all its guises becomes a pop music dissertation on the subject, dissecting and analyzing one of pop culture’s most celebrated emotions through perfectly rendered character sketches, witty soliloquies, and gorgeous, straight-up pop songs. Much has been made over the years of the biting irony that runs through much of Merritt’s songwriting, but what becomes clear across the song’s on 69 Love Songs is that the irony becomes, when present, for each song’s speaker, an access point into pure, earnest emotion. This is most obvious on a song like “The Book of Love,” which finds its speaker poking fun at the book in question for being “long and boring” and packed with “dumb” music, before ultimately proclaiming, “I love it when you read to me and you can read me anything,” dismissing the cynicism and self-aware attitude for sweet sincerity. Of course, no discussion of 69 Love Songs would be complete without mentioning Merritt’s deep bench of supporting musicians, including Claudia Gonson, LD Beghtol, Dudley Klute, and Shirley Simms, among others, who bring many of Merritt’s characters to life with guest vocals. Ultimately, 69 Love Songs isn’t just a great pop album, it’s a monument to pop’s persistent obsession with romance, an honest account of love and its many permutations, while simultaneously being a critique of our cultural construction of romantic love. Plain and simple, 69 Love Songs could and probably should be a pretentious train wreck, but Merritt’s deft songwriting allows it to transcend the trappings of its concept to become one of the great, towering and iconic albums of late twentieth century pop. –James Brubaker

Also Recommended: The Magnetic Fields The Charm of the Highway Strip (1994) and Get Lost (1995), The Shins Oh, Inverted World (2001), The Decemberists Castaways and Cutouts (2002), and Her Majesty The Decemberists (2003), Saturday Looks Good to Me Saturday Looks Good to Me (1999), All Your Summer Songs (2003), Every Night (2004), Fill Up the Room (2007).

029 | Talk Talk | Laughing Stock

[Verve/Polydor, 1991]

After a slew of UK hits in the mid-1980s, anchored by the popular tune “It’s My Life” (later a hit cover by No Doubt), Talk Talk decided to blow out the record company’s budget on an impressionistic album completely bereft of radio-friendly material titled Spirit of Eden in 1988. The album sold poorly, but was quite influential in some corners of the musicsphere. It was a polarizing release. In fact, the 1992 edition of the Rolling Stone Album Guide gave it a 1-star review. After getting bounced from EMI because of poor sales, Talk Talk’s last stand proved to be their 1991 swan song Laughing Stock, an album that went all in with the approach found on Spirit of Eden. Now fully accustomed to writing sketches rather than songs—sketches eschewing the verse chorus verse bridge verse coda-style formulas of traditional rock and pop music—Talk Talk’s two masterminds, Mark Hollis and producer Tim Friese-Greene, increase the space between instruments, leaving only the skeletal remains of songs. The one exception is “Ascension Day,” which proves to be their greatest single song, even better than “It’s My Life,” dominated by aggressive, dissonant rhythm guitar playing. The remainder of the tracks on the album draw on ambient, avant-garde, and chamber music elements. This quiet, yet oddly propulsive album was, again, a commercial failure that effectively ended the group. But its influence has grown immeasurably over the years. It has become hailed as a precursor to the “post-rock” genre and seen as a likely influence on Radiohead. By minimizing the emphasis on a backbeat and maximizing the attention of musical textures, Talk Talk, with Laughing Stock, created idiosyncratic, inimitable music completely outside the time that produced it. –Brian Flota

Also Recommended: Mark Hollis Mark Hollis (1998), Talk Talk The Colour of Spring (1986) and Spirit of Eden (1998)

028 | Slayer | Reign in Blood

[Def Jam, 1986]

Def Jam Recordings, founded by mogul Russell Simmons and revered producer Rick Rubin, started in the mid-1980s with a focus mainly on hip-hop. They made LL Cool J and the Beastie Boys international superstars. When somebody wasn’t looking, Rick Rubin signed the thrash metal band Slayer to the roster. Rubin was on to something. Slayer had made a name for themselves with two solid but amateurishly produced albums (1983’s Show No Mercy and 1985’s Hell Awaits) and two EPs on the Metal Blade label. Once paired up with Rubin, Slayer trimmed away the compositional excesses found on their earlier records, tightened up their sound, and increased the speed (thanks to drum whiz Dave Lombardo). By injecting the influence of hardcore punk into their traditionally metal palette, Slayer became a beast. Their first album on the Def Jam label, Reign in Blood, stands as a hallmark of speed metal. Its intensity and concision (it clocks in at 28 minutes) has rarely been matched since. Boasting one of the greatest album openers of all time in “Angel of Death,” one of only two songs on the album that cross the three-minute mark, the group highlights their affinity for blistering tempos, the insane guitar stylings of Jeff Hannemann and Kerry King (who during solos often sound like they are playing another song in a different studio), and intentionally shocking (yet often silly) lyrics that had the potential to land them in hot water with critics on both the right and the left. Released during the height of the “Satanism Scare” of the 1980s, Slayer exploited this fear for all it was worth in their lyrics, making references to Josef Mengele in “Angel of Death,” “spilling the pure virgin blood,” entering the “realm of Satan” in “Altar of Sacrifice,” and noting that it’s “raining blood, from a lacerated sky, bleeding its horror” in the epic closer “Raining Blood.” In the hands of lesser acts, this material could easily fall flat. But Slayer sells its lyrical content, thanks to the aptly metal vocals of bassist Tom Araya like Billy Mays doing an infomercial. Framed by two of metal’s greatest songs in “Angel of Death” and “Raining Blood,” Reign in Blood is an impeccably sequenced album with relatively little filler. The album proved so good that it became a trap for Slayer, who, in the thirty-plus years since the album was released, have rarely strayed from the musical template laid down here. While Metallica would prove to be more tuneful and musically sophisticated than Slayer, nobody could best Slayer as a straight-ahead thrash metal band. –Brian Flota

Also Recommended: Flotsam and Jetsam Doomsday for the Deceiver (1986), Slayer South of Heaven (1988), Seasons in the Abyss (1990), Decade of Aggression (1991), Divine Intervention (1994) and God Hates Us All (2001), Voivod Dimension Hatross (1988)

027 | William Basinski | The Disintegration Loops

[2062, 2002]

We’re all going to die. That’s the basic truth on which William Basinski’s ambient masterpiece The Disintegration Loops hinges. By now, I’d imagine most of us know the story, but in case you haven’t encountered this masterpiece, here’s the short version: Basinski was digitizing ambient tape loops he’d made in the early 80’s when he discovered the iron ferrite of the tapes was rubbing off in the process; so, he recorded the loops for long periods of time so that as each loop repeats, listeners can hear the disintegration of the physical tape itself, calling to mind the mortal decay of our slow march toward death. Basinski’s compositions are built on a quiet sense of beauty, so at least, you know, as we begin our death spirals, we have a reason to go on, or something. There are other associations at play, here, between this album and 9/11 (something about Basinski listening to the album on his rooftop and filming the smoke from the attacks, from which images were pulled for the album covers)—and I guess that makes sense, if we tie the physical decay of the tapes to the spiritual and psychic rot of American culture. Hypnotic, gorgeous, and contemplative, Basinski’s Disintegration Loops accompanied me on many late night walks around Stillwater when I was working on my Ph.D., there, and continues to be in regular rotation at my “writing desk.” The truth is, there isn’t a lot to say about The Disintegration Loops, beyond “it’s a series of ambient loops repeated through their decay for long periods of time”—no, this is an album that needs to be experienced, that needs to be felt. The first time I listened to it, I was stunned at how affecting such minimal music could be. I sat, stunned, as I listened to the tape’s decay play out through my headphones, and when the first track ended, I realized I’d been sitting still, not doing anything but listening, for an hour, enraptured by the beauty and sorrow flowing running through the recording. –James Brubaker

Also Recommended: The Caretaker An Empty Bliss Beyond This World (2011), Tim Hecker Ravedeath, 1972 (2011) and Virgins (2013), Fennesz Black Sea (2008), Stars of the Lid The Tired Sounds of Stars of the Lid (2001) and And Their Refinement of the Decline (2007).

026 | N.W.A | Straight Outta Compton

[Ruthless, 1988]

The last few years have been kind to N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton, thanks to the extremely popular F. Gary Gray biopic of the same name released in 2015 and the recent HBO mini-series The Defiant Ones (about Beats co-founders Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine), which spent plenty of time discussing the importance of the album. When the album came out in 1988 it sparked instant controversy–culminating in the FBI sending a letter to N.W.A’s label, Ruthless Records, voicing their issues with the album. The notoriety of the album put West Coast rap on the map and made stars of Eazy-E, Ice Cube, and producer/rapper Dr. Dre. Straight Outta Compton’s combination of shock value descriptions of violence (often directed at the police), wealth, misogyny, and general contempt for authority widely separated them from the popular hip-hop acts of the day (like Run-DMC, the Beastie Boys, LL Cool J, and DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince). Co-producers Dr. Dre, DJ Yella, and the Arabian Prince fused booming beats with samples that are both funky and sinister. Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols might have once been considered a threat to popular music’s status quo, but it’s got nothing on the first three songs found here. “Straight Outta Compton,” “____ tha Police,” and “Gangsta Gangsta” are three of the strongest, boldest, craziest, and dangerous tracks to start any album. Here’s a taste of some of the lyrics: “When I’m in your neighborhood, you better duck / ‘Cause Ice Cube is crazy as fuck”; “When I’m finished, it’s gonna be a bloodbath / Of cops, dying in LA”; or, “Takin’ a life or two, that’s what the hell I do / You don’t like how I’m livin’, well fuck you.” Prior to these records, pop music was occasionally graced with some of George Carlin’s seven words you can’t say on television. But nothing like what’s on Straight Outta Compton. The “foul language” factor is not the only thing striking about the record. With this collection of songs, N.W.A frankly describes the reality and the fantasy of life in Los Angeles’s and Compton’s primarily black neighborhoods at the moment crack was ravaging the African American community in cities all across the United States. The world N.W.A captures here is consumed by the illegal drug trade, military-grade firearms, instant sexual gratification, and police brutality. This world was willingly ignored by the (white) American mainstream, and N.W.A gave it an authentic and abrasive voice in popular culture that made it something the mainstream could no longer willfully ignore. Given the confrontational excellence of the album’s trio of opening tracks, it’s hard for Straight Outta Compton to sustain that momentum throughout. Tracks like “If it Ain’t Ruff” and “Quiet on tha Set” are generic dance numbers, and it’s hard to excuse the full-bore misogyny of “I Ain’t tha 1.” However, lesser tracks like the hit (and their obscenity-free attempt at positivity) “Express Yourself” and the relatively minimal “Compton’s n the House” get that head bobbin’. Warts and all, few albums in the last thirty years have had the impact of Straight Outta Compton. Though it didn’t invent “gangsta rap” (most people claim Schooly D’s 1985 single “P.S.K. [What Does it Mean?]” is the first gangsta rap song), it popularized it and spawned tens of thousands of imitators. –Brian Flota

Also recommended: The D.O.C. No One Can Do It Better (1989), Freddie Gibbs and Madlib Piñata (2014), Ice Cube Death Certificate (1992) and The Predator (1993), Ice-T OG Original Gangster (1991), 2Pac All Eyez on Me (1996)

025 | Frank Ocean | Blonde

[Boys Don't Cry, 2016]

I know, I know—the last thing this list needed was another album from 2016. And, I know, I know—it’s probably less than ideal that the album arrives higher than that year’s two more visible, important albums from the sisters Knowles, Lemonade and A Seat at the Table. Here’s the thing—while each of those albums is important, impressive, and wonderful, with Blonde, Frank Ocean has created music unlike pretty much anything else in pop music. Sure, there are some pop signifiers running through the album, but the end result ends up being one of the most intimate and vulnerable albums ever released by a major pop star. Granted, referring to Ocean as a major pop star belies the essential nature of Blonde. Despite the lush strings and piano of “Pink + White” and the warm production and chipmunk vocals of album opener “Nikes,” Blonde is a stealth anti-pop album—returning melodies are few and far between, and hooks are fewer and farther. The result is a restless, searching album that finds Ocean singing as if from a quiet corner of a dark bedroom. The vivid characters and narratives that defined Ocean’s proper debut, Channel Orange have been replaced by impressionistic first person ruminations on love, memory, nostalgia, and loss—so maybe it’s Pet Sounds for a new generation? Hell, there’s even a reference to cutting hair, vaguely recalling “Caroline No”: “You cut your hair but you used to live a blonded life/Wish I was there, wish we'd grown up on the same advice/And our time was right.” This lyric, like many others on the album, are just specific enough evoke something concrete and real, but vague enough to allow a space into which listeners can easily enter and write their own stories. Even when Ocean does return to storytelling mode, as he seems to do on the stunning “Solo,” which finds characters escaping their loneliness through substances, the stories aren’t necessarily about a single character, and are conveyed in bits of fragmented narration, getting to the emotional truths of the characters’ inner lives rather than detailed story telling—whole worlds spiral out of brief moments. Ultimately, what makes Blonde so affecting is its approach to sharing. At times, Ocean’s voice comes across as little more than a whisper, as he winds elliptical lyrics over delicate arrangements that rarely draw attention to themselves, creating a stunning and reflective vulnerability, as if Ocean is performing just for you. In so far as Blonde doesn’t sound like any other album in its genre, and in so far as it celebrates (and, to be fair, questions) the inherent intimacy of a sharing culture, I can’t think of an album more revelatory, revolutionary, and of the moment, while still keeping an eye on the future. –James Brubaker

Also Recommended: Frank Ocean NostalgiaULTRA (2011) and Channel Orange (2012), Miguel Kaleidoscop Dream (2012) and Wild Heart (2015), DVSN Sept 5th (2016), Jeremih Late Nights (2015), The Internet Ego Death (2015), Blood Orange Freetown Sound (2016).

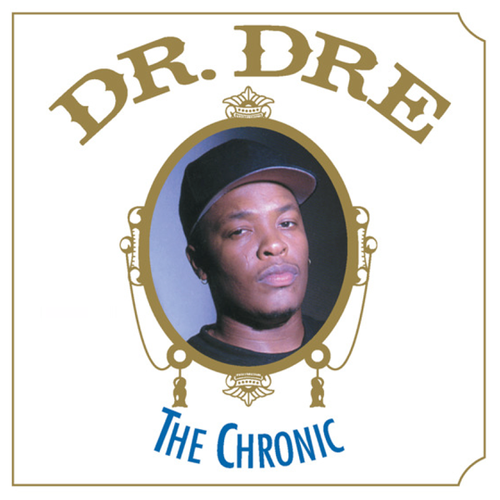

024 | Dr. Dre | The Chronic

[Death Row, 1992]

Following the dissolution of N.W.A, that group’s main producer, Dr. Dre, was going to have to strike out on his own without the talents of Ice Cube–who had recently launched a successful solo career–and Eazy-E, the mastermind behind N.W.A. Because of financial disputes, the relationships between these stars became testy and personal. Ice Cube, for one, launched attacks against N.W.A and their manager Jerry Heller on his first two albums. Now deprived of the most talented rapper in N.W.A, Dr. Dre, a competent but far from virtuoso-quality rapper, would have to magically find someone who was Ice Cube’s equal. Thankfully, Dr. Dre discovered a young man named Calvin Broadus, also known as Snoop Doggy Dogg, who had a distinctive, laid back flow and knew his way around a turn of phrase. He also had the attitude to match. Now in charge of his own project, Dr. Dre devoted his attention to the production and sound engineering of the album that would soon become The Chronic. By recreating samples with live musicians and focusing on melodies, Dr. Dre began to create completely infectious gangsta rap tunes. That is the major innovation on The Chronic, an album that lacks the lyrical bluntness of Straight Outta Compton but completely bests it (and most other albums) with a sonic sophistication and clarity far beyond any of its peers. The album’s highlight (and biggest hit), “Nuthin’ but a ‘G’ Thang,” is a summer anthem about chasing (and objectifying) women, adopting a macho pose, talking shit, smoking potent weed, and having fun. Snoop Dogg’s flow is utterly captivating, filled with captivating wordplay and a silky confidence rare in a newcomer. Snoop is the album’s not-so-secret weapon, writing about 75% of its lyrics. Not to be outdone is Dre’s production, which is filled with crystal clea bass, as if the band is in the same room you are in. The Chronic would go on to boast two other huge hits in “Dre Day” and “Let Me Ride,” both rocking huge PFunk samples. “Dre Day” exacerbates the feud between Dre and Eazy-E, a (somewhat childish) lyrical leitmotif throughout the album. Other tracks on the album (“The Day the Niggaz Took Over” and the skit “The $20 Sack Pyramid”) playfully comment on the LA uprising that followed the Rodney King verdict on April 29, 1992. The album has few valleys and is one of the most consistent from the era, thanks in part to Dre’s instinct for generating earworm hooks and a selection of tasty samples (ranging from Donny Hathaway and Led Zeppelin to Malcolm McLaren and Willie Hutch). The album’s celebration of gangsta life and its unflinching misogyny garnered it criticism from across the political spectrum at the time. Though Straight Outta Compton put gangsta rap on the map, The Chronic made it a staple of the pop music landscape for the next few decades, perhaps because of these very controversies. Twenty-five years later, The Chronic stands as one of hip-hop’s enduring monuments, permanently enshrining Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg as pop culture icons. –Brian Flota

Also Recommended: Dr. Dre Compton (2015), Snoop Doggy Dogg Doggystyle (1993), Eminem The Marshall Mathers LP (2000).

023 | Arcade Fire | Funeral

[Merge, 2004]

Was Arcade Fire’s Funeral the last big push that finally triggered indie rock’s ascendance to the mainstream? Was it the tipping point for Pitchfork, whose 9.7 review of the album seemed to demonstrate how much influence the site was beginning to exert on popular music? Was it a wildly affecting set of songs, obsessed with human connection and the infectiousness of youth? Well, it was all of those things, and it still stands as a monument to what great records can do and be, from a time when the genre was exhausted and unsure of itself. Looking back, Funeral sounds quaint and surprising in light of how Arcade Fire has evolved. After more than a decade of increasingly slick album production and a steady stream of mostly classic/near-classic albums, revisits to Funeral can feel surprisingly visceral. Here, what we now understand as Butler and company’s bombastic impulses and big ideas come through in raw vocal performances and punk energy. Just a few years later, on this album’s follow up Neon Bible, the band would already begin trading that energy, sometimes for better, sometimes worse, for big arrangements and bigger ideas. And, as well as an album like The Suburbs has aged, and as beautifully slick and crafted as Reflektor continues to be, Funeral is still the easy highlight of Arcade Fire’s career. From Butler’s raw, urgent vocal performance on album opener “Neighborhood #1 (Tunnels),”it’s clear that Arcade Fire is a force to be reckoned with. As the album progresses, the band treats us to an array of sounds and styles, from the delicate quiet of“Une année sans lumière,” to the regal and gorgeous “Crown of Love,” to the triumphant, heard-it-in-every-commercial-through-the-mid-00’s anthem that is “Wake Up.” While the Pitchforks and the music nerds of the world knew Funeral was special upon its release, I’m not sure anyone really knew how timeless the album would be. All these years later, it’s become abundantly clear that Funeral isn’t just one of the best and/or most influential albums of the 00’s, but is one of the best “indie” rock albums of all time. And for all of its great songs, the album’s finest moment remains that opening track, for its sheer celebration of youthful exuberance in the face of heartache: “And if my parents are crying/Then I'll dig a tunnel/From my window to yours/Yeah, a tunnel from my window to yours.” As the song’s protagonists fantasize their future escape from whatever it is that makes their parents cry, Arcade Fire provide one of the purest, most beautiful expressions of youthful optimism ever committed to record. –James Brubaker

Also recommended: Arcade Fire The Suburbs (2010) and Reflektor (2013), The National Boxer (2007), Band of Horses Everything All the Time (2007), Broken Social Scene You Forgot it in People (2002), Clap Your Hands Say Yeah Clap Your Hands Say Yeah (2005), Grizzly Bear Yellow House (2006) and Veckatimest (2009), The War on Drugs Lost in the Dream (2014).

022 | Pavement | Slanted and Enchanted

[Matador, 1992]

After a spate of cult-classic and highly collectible EP releases in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Pavement burst onto the indie scene in a big-time way with their debut LP Slanted and Enchanted. Following the unexpected success of Nirvana’s Nevermind, whose success jump-started discussions about “Generation X” and the so-called “slackers” that supposedly populated this group, record labels were on the lookout for like-minded artists. While most of the major labels went after “grunge” acts like Nirvana, Chris Lombardi and Gerard Cosloy’s fledgling Matador Records already had several quirky, jangly indie-rock bands in its stable. Pavement fit their bill because of frontman Stephen Malkmus’s penchant for lyrical non-sequiturs and off-kilter guitar riffs. The group parodied the seriousness of the American underground music scene at the time, whether it was the political determination of groups like Fugazi and R.E.M. or the sheer volume of acts like Dinosaur Jr. and Sonic Youth, and generated a playful, sloppy, experimental, and poppy aesthetic that wowed fans and perplexed the masses at the time. Slanted and Enchanted opens with one of the catchiest tunes of the era in “Summer Babe (Winter Version),” which effectively announces the group’s approach–lo-fi production, a first-take apathy towards instrumental precision, a lyrical delivery embodying Frederic Jameson’s notion of postmodern “blank parody,” and, beneath all that substantial window dressing, an unconventional but highly effective knack for delivering pop hooks. “Trigger Cut” which follows, is nearly as catchy. “No Life Singed Her” is Pavement’s straight-ahead parody of the recent grunge fad, replete with Cobainesque screaming, and manages to once again tap into the group’s uncanny ability to make ANYTHING catchy, as is their Fall rip-off (“A New Face in Hell”) “Conduit for Sale.” The group displays its versatility on the album by channeling country music on “Zurich is Stained” and balladic pop on one of the record’s highlights, “Here.” They even get involved in a political issue on “Two States,” a hilarious send-up of a long-forgotten California ballot proposition in the early 1990s to make California into two states (Northern and Southern California). Slanted and Enchanted captures the group at their most raw (discounting their earlier EPs, which were subsequently collected on Westing [By Sextant and Musket]). Many fans of the group prefer their later, comparatively slicker albums (especially Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain and Brighten the Corners). But for this writer, Slanted and Enchanted remains Pavement’s–and one of the era’s–defining album-length musical achievements. – Brian Flota

Also recommended: Built to Spill Perfect from Now On (1997), Pavement Wowee Zowee (1996), Superchunk Here’s Where the Strings Come In (1995), The Mountain Goats Zopilote Machine (1994), Hüsker Dü Warehouse: Songs and Stories (1987)

021 | GZA/Genius | Liquid Swords

[Geffen, 1995]

Wu-Tang Clan’s 1993 debut Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) is without a doubt one of the most important and influential albums of the last 25 years. The first solo album by the GZA, Liquid Swords, is arguably the better album. Bolstered by the RZA’s production, which is even better here than on Enter the Wu-Tang, the GZA and the RZA continue to develop the most compelling musical universe since the height of the PFunk era in the 1970s. The cover art, by comic book artist Denys Cowan (a co-founder of Milestone Comics, the most widely distributed African American-owned comic book company to date), adds even more flair to the Wu-Tang universe, one heavily informed by martial arts movies (in particular 1980’s Shogun Assassin, Robert Houston’s “mash-up” of the first two Lone Wolf and Cub films) and drug dealing, resulting in a cinematic aesthetic filled with sympathetic anti-heroes. The RZA continues his development as one of hip-hop’s unquestionably greatest producers on Liquid Swords, again mining old soul records for ominous, disorienting loops. Guest spots from ODB, Inspektah Deck, Ghostface Killah, Raekwon, Killah Priest, Method Man, and U-God essentially make this a Wu-Tang Clan album, which is not a bad thing! What separates this album from Enter the Wu-Tang is its tone. While that record was loaded with plenty of humor, Liquid Swords is comparatively quite humorless, the tone weighty and ominous. The mob movie-inflected lyrical details in songs like “Duel of the Iron Mic,” “Hell’s Wind Staff/Killah Hills 10304,” and “I Gotcha Back,” combined with the almost atonal horn and piano loops deployed by the RZA, present a world where danger is probably lurking around every corner. Because of the record’s medley of influences, this frightful landscape never succumbs to the dour weight of the seriousness they suggest. Despite being a CD-era product clocking in at nearly an hour in length, Liquid Swords is remarkably paced and, as a result, never overstays its welcome. Though the album might lack the understandable impact of Enter the Wu-Tang, and can never fully escape its shadow (as this review makes painfully clear), it is a glorious companion piece to one of the most vibrant and communally inventive explosions of creativity in the annals of popular music. – Brian Flota

Also Recommended: To be honest, we couldn’t come up with anything that we haven’t already listed yet, or don’t plan to list on future posts. So, if you want a recommendation, here, just go revisit Enter the Wu-Tang, and maybe some Ghostface and RZA albums or something.

100-86 | 85-71 | 70-61 | 60-51 | 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-21 | 20-11 | 11-2