First of all, we’d like to thank the new Collapsar team for allowing us to finish up this little list we started. The schedule might be a little different, we’ll still bring the noise. Speaking of, this installment of our list moves even further away from “unexpected” territory, including some seminal hip hop albums and a few beloved and influential indie rock staples. Of course, there are still a couple of surprises here: that we’re excited to list alongside some of the more expected entries. So, once again kick back, relax, fire up your favorite music streaming service of choice, and spin some tunes with us.

040 | Guided by Voices | Bee Thousand

[Scat, 1994]

By the time Robert Pollard and whichever of his Guided by Voices “bandmates” were working on the album that would become their breakthrough, Bee Thousand, Pollard was thirty-six years old. The band had almost broken up once, was again close to calling it quits, and everyone was a little freaked out at the prospect of following up Propeller and Vampire on Titus, GBV’s highest profile albums up to that point. Somehow, through some combination of mining old, unreleased songs and churning out a batch of exceptional fresh cuts, Pollard and co. sculpted not only one of his own band’s best albums, but one, if not perhaps the best lo-fi album of all time. Arriving hot on the heels of Pavement’s early, lo-fi-ish work, and after incubating in the relative obscurity of Dayton, Ohio’s late 80’s and early 90’s music scene, GBV elevated the stakes of the lo-fi aesthetic, the result being an, at turns gorgeous and ugly collage of songs as clear as only the white noise they’re fighting against would let them be. Perhaps the truly remarkable thing about Bee Thousand (and about Pollard’s music, in general) is that, buried in that magnificent, noisey collage is an unfuckwithable sense of joy; Pollard isn’t just an expert tunesmith churning out fragments of British Invasion Era Pop like so many puzzle pieces in a messy lo-fi medley—no, he’s a passionate fan of pop music history. Peppered throughout the album’s twenty songs are nods to The Beatles, The Kinks, The Who, Cheap Trick, Big Star—GBV’s songwriting influences, here, are a veritable who’s who of American and English powerpop, and GBV gives it to us in the best way possible—hissy and messy, as if playing from a dying AM radio from two rooms away or out of the car in front of you at a stoplight. Bee Thousand isn’t just the quintessential lo-fi masterpiece, it’s the album that saved Pollard and GBV’s careers, making possible literally thousands of fantastic songs we’d have never heard had Pollard retired his rockstar dreams and settled into the life of a teacher. And, of course, it gave us songs as beloved and timeless as “Tractor Rape Chain,” “Echoes Myron,” and “I Am a Scientist.” Bee Thousand was a stunning album upon its release, all these years later, it seems like just another day at the office for Pollard, though that day in the officer’s influence has been profound.

--James Brubaker

Also Recommended: Guided By Voices Propeller (1992), Vampire on Titus (1993), Alien Lanes (1995), Isolation Drills (2001), and Earthquake Glue (2003), Robert Pollard Not in My Airforce (1996), Robert Pollard with Doug Gillard Speak Kindly of Your Volunteer Fire Department (1998), Boston Spaceships Zero to 99 (2009), Ween The Pod (1991), Sebadoh Bakesale (1994).

039 | The Flaming Lips | The Soft Bulletin

[Warner Bros., 1999]

How odd that Bee Thousand and The Soft Bulletin landed back to back on this list. Like with Bee Thousand, The Soft Bulletin was the product of a band at a crossroads, unsure what to do next, and ultimately releasing the best album of its career. Of course, The Flaming Lips kicked around for sixteen years before making their masterpiece, and not all of that time was spent in relative Oklahoma City obscurity, thanks to a buzz bin worthy spot for the Lips’ infectious 1994 not-quite hit, “She Don’t Use Jelly.” Still, after going four years without a release following the excellent psychedelic guitar-pop of Clouds Taste Metallic, which didn’t make much noise upon release, nobody was really expecting the Lips to show up, practically out of nowhere, and drop an indie rock masterpiece on us as if they had something to prove. But that’s the thing—they did have something to prove. After the brief buzz blip that was “She Don’t Use Jelly,” off of Transmissions From the Satellite Heart, and that album’s follow up’s inability to get any traction on radio or MTV, the Lips were widely seen, despite, at the time, having seven albums of aggressively weird psychedelic rock, as a one hit wonder. Thanks to The Soft Bulletin, though, and with the help of orchestral psyc-pop producer extraordinaire, Dave Fridmann, Coyne and co. managed to shake that tag for good. Geared more towards orchestral psychedelia than the guitar flavored rock they’d previously embraced, the album softened the band’s harder, weirder edges, and sounded just familiar enough to be inviting for music fans across generations. That is to say, The Soft Bulletin feels as much like something Van Dyke Parks might have released in 1967 as the lips would have in 1997, landing like a familiar but strange UFO at the height of an era that worshipped at the alter of symphonic rock. That’s not to say the Lips went “soft” though—despite the warm arrangements, these songs are still about shit like drug usage (“Spiderbite”) and existential dread (“Suddenly Everything Has Changed”), the packaging was just a bit different—it went down a bit smoother. Here’s the takeaway, The Soft Bulletin is a masterpiece, the warmer, fuzzier, weirder answer to Radiohead’s overrated OK Computer. With Bulletin, The Lips went a long way towards building on what Radiohead had done two years before, and Wilco would continue to build on: laying a foundation for indie rock’s eventual big tent takeover of popular culture—and they did it with the best album of their career.

--Brian Flota

Also Recommended: The Flaming Lips Hit to Death in the Future Head (1992), Transmissions from the Satellite Heart (1993), Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots (2001), Blur The Great Escape (1995), 13 (1999), Ween The Mollusk (1997), Tame Impala Lonerism (2012), Mercury Rev Deserter’s Song (1998), The Olivia Tremor Control Music From the Unrealized Film Script, Dusk at Cubist Castle (1996).

038 | Dinosaur Jr.| You’re Living All Over Me

[SST, 1987]

Once American hardcore punk in the mid-1980s began to split into various factions less hostile to classic rock and heavy metal styles, Dinosaur Jr. was presented with a huge opening. By fusing the punk aesthetic that prevailed in the American underground over the previous decade with that same period’s guitar god heroics, Dinosaur Jr. became one of the shining lights of “alternative rock.” Maintaining the scuzzy aesthetic of the best punk records, Dinosaur Jr.’s best songs over the next five years or so deliver nearly as much noise as The Jesus and Mary Chain’s Psychocandy (1985), though they largely eschew that group’s pop instincts. To be fair, J Mascis, the group’s frontman, can yield some catchy gems from time to time, which is one of the reasons why certain people, the kind who hail from “ear bleeding country,” love them so much. After an effective debut LP (1985’s Dinosaur), the trio, anchored by the wonderful rhythm section of Murph on drums and Lou Barlow (later of Sebadoh fame) on bass, Dinosaur delivers their first classic with You’re Living All Over Me. On it, Mascis largely eliminates the influence of R.E.M. found on their first album and fully realizes his own vision as a songwriter. While powerful numbers like opener “Little Fury Things” and “In a Jar” have a touch of that jingle-jangle, it emanates from a swirl of noise grounded by a fast and furious rhythm section. Thanks (or, rather, no thanks) to the production of Wharton Tiers, a tin-eared approach to production emerges, which is not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, it is a strength, as it draws attention away from Mascis’s rather limited vocal range. This also manages to bring the Raw Power sound into the 1980s, allowing Mascis’s dynamism as a wah-wah-fueled guitarologist to shine, especially on a number like “Sludgefeast.” On that song, the brilliance of the rhythm section becomes apparent. Though the song isn’t all that fast, Murph’s drumming makes it sound faster than an early Minor Threat number. The track, which foreshadows elements of the “grunge” sound, is lousy with guitar noise, and it’s fantastic. Mascis even lets Lou Barlow loose on the album’s last two songs, which would sink a lesser album. Thanks to the album’s blend of white noise, pop hooks, and guitar ferocity, You’re Living All Over Me emerges as one of the era’s best records. –Brian Flota

Also Recommended: Dinosaur Jr. Bug (1988) and Farm (2009), My Bloody Valentine Isn’t Anything (1988), Sebadoh Bakesale (1994), Neil Young and Crazy Horse Psychedelic Pill (2012)

037 | Bikini Kill | Pussy Whipped

[Kill Rock Stars, 1993]

The American Hardcore punk scene, which crystallized in the early 1980s, maximized punk’s musical attention to anger, fury, and aggression. While, at its best, this was a gloriously cathartic and political development, meant to provoke the ire of the Reagan-era mainstream, it was an overwhelmingly masculine (and heteronormative) affair. At shows, the boys moshed like football players. The performers were practically all male. Revered acts like Black Flag (who had a female bass player, Kira Roessler, for a few years) have misogynist lyrics on some of their most notable songs (see “Slip it In”). Though punk was supposed to reject conformity and the status quo, it ended up reaffirming the mainstream values of the patriarchy. Though the UK punk scene of the 1970s had numerous female figureheads (Siouxsie and the Banshees, X-Ray Spex, The Slits, and The Raincoats, to name but a few), the American scene was embarrassingly phallocentric by comparison. In the early 1990s, punk was making a comeback of sorts, thanks in part to a vibrant scene of musicians from the Northwest. One of the most crucial bands in this scene was Olympia, Washington’s Bikini Kill, who felt the male-dominated world of rock and punk was long overdue for a talking to. By eliminating the heavy metal trappings of more recent punk music, returning the music to its “three chords now form a band” approach, and informing their lyrics with the philosophy of Third Wave feminism, Bikini Kill made an immediate impression. Kathleen Hanna’s compelling stage presence and confrontational vocal style is given the perfect complement by Tobi Vail’s hyper-direct drumming, Kathi Wilcox’s melodic, floor-rumbling basslines, and Billy Karren’s scabrous guitar. After a cassette demo and two fantastic EPs, Bikini Kill delivered their first LP, Pussy Whipped, in 1993. Though grunge was getting mainstream audiences, Bikini Kill was at the center of the riot grrrl movement, along with other notable groups such as Bratmobile, Heavens to Betsy, and Sleater-Kinney. Pussy Whipped finds the group at the peak of their powers, delivering incisive, explosive tracks like “Alien She,” “Magnet,” and “Speed Heart.” One visceral highlight is “Star Bellied Boy,” whose lyrics are about a rapist who portrays himself as a sensitive hipster dude who’s really “no fucking different from the rest,” culminating with Hanna screaming “I CAN’T CAN’T CAN’T CUM.” The most popular song on the album is one of three versions of “Rebel Girl,” and this might be the best of the lot, proving the group know how to make a catchy anthem, one that celebrates women who have rejected patriarchal values and give zero fucks about it. The album closes with a discordant ballad dedicated to the artist Tammy Rae Carland (who took the cover photo). The fact that the excellent Pussy Whipped still rarely makes it into these types of lists–especially those solely focused on punk rock–proves that Bikini Kill’s critique was, and, unfortunately, is still correct. We all have plenty to learn from this album. –Brian Flota

Also recommended: Bikini Kill Bikini Kill (1992), Bikini Kill/Huggy Bear Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeah/Our Troubled Youth, Bratmobile Pottymouth (1993), Le Tigre Le Tigre (1999), Julie Ruin Julie Ruin (1998), Sleater-Kinney Call the Doctor (1995)

036 | Neutral Milk Hotel | In the Aeroplane Over the Sea

[Merge, 1998]

As soon as Jeff Mangum’s voice enters over the opening strums of “King of Carrot Flowers pt. 1,” it’s immediately clear that In the Aeroplane Over the Sea is a special album. Upon its release in 1998, it wasn’t a particularly innovative album, and it didn’t garner a ton of attention. However, fueled in part by Mangum’s stepping away from music, but mostly by the album’s sheer brilliance, this ambitious and lovely set of songs grew its status the old fashioned way, through word of mouth and mixtapes. I didn’t come across the album until around 2001 or 2002 when a guy with whom I was in a screenwriting class, upon hearing I’d never heard the album, played it for me while we were hanging out at his house. I was instantly taken with Mangum’s songs and bought the album the next day. Ask just about anyone how they came to In the Aeroplane Over the Sea and odds are you’ll hear a story like mine. Now, the album is one of the most beloved indie rock albums of all time, and it deserves every ounce of that success and acclaim. Sure, the angle that gets the most play in discussions of the album is its being about Anne Frank, but the real reason it resonates so deeply isn’t because of its concept, but because of how raw and earnest it all feels—these are songs about growth and discovery, about sex and death. In “King of Carrot Flowers pt. 1,” the two young protagonists “lay and learn what each other’s bodies are for.” When Mangum sings “We will take off our clothes” on “Two-Headed Boy,” his voice thrums with a raw, electric sexual urgency. But it isn’t all about sex—sure, this album’s world is one in which “semen stains the mountain tops,” but it’s also one where a brother “rides a comet’s flame,” a speaker imagines a romantic partner as a puppet, remembering how he would “push his fingers through/Your mouth to make those muscles move,” and in which Anne Frank is described as being born, “With wings that ringed around a socket right between her spine.” And, sure, maybe the crux of the album is an examination of loneliness against a back drop of the memory of Anne Frank, but that exploration is utterly ecstatic and bursting with life, making In the Aeroplane Over the Sea a masterful examination of human connections and desire. –James Brubaker

Also Recommended: Neutral Milk Hotel On Avery Island (1996), Apples in Stereo Tone Soul Evolution (1997), Elf Power The Winter is Coming (2000), Circulatory System Circulatory System (2001), Bright Eyes Lifted -or- The Story is in the Soil Keep Your Ear to the Ground (2002), The Mountain Goats The Sunset Tree (2005),

035 | The Pixies | Doolittle

[4AD, 1989]

At this point, it’s easy to take The Pixies for granted. They’ve been a part of “indie culture” for thirty years and have influenced so much of that culture it’s easy to forget that they basically pioneered the deft mixture of pop and punk, sweet and unhinged, loud and quiet, that influenced rock music from the ground up, from Nirvana to your little brother’s band who will play eight shows, release a seven inch and break up when the members all go to different colleges. To this day, I’m hard pressed to think of a vocal duo as perfectly matched as Kim Deal and Black Francis—the mixture of Deal’s clean voice with Francis’s abrasiveness buoys the album’s already palpable sense of tension through its fifteen killer songs, opening with the unhinged “Debaser,” all the way through immaculate “Gouge Away.” Along the way, The Pixies treat us to such classics as “Wave of Mutilation,” “Here Comes Your Man,” “Monkey Gone to Heaven,” “I Bleed,” “La La Love You,”—I could go on, but I’d just end up listing the entire album. Of all those great songs, and this might seem a bit counterintuitive, it’s “Here Comes Your Man” that best encapsulates The Pixies’ project—rather than lean into the sonic dynamics that many have come to associate with the band, here, the song achieves the same effect by juxtaposing cloying pop with grim lyrics about train hoppers and drunks dying in an earthquake. Sure, the song doesn’t include any guitars turned up to eleven or big screams, but in the space between the arrangement and the lyrics a haunted sadness emerges and resonates. –James Brubaker

Also recommended: Belly Star (1993), Pixies Surfer Rosa (1988), Bossanova (1990) and Trompe Le Monde (1991), The Breeders Last Splash (1993)

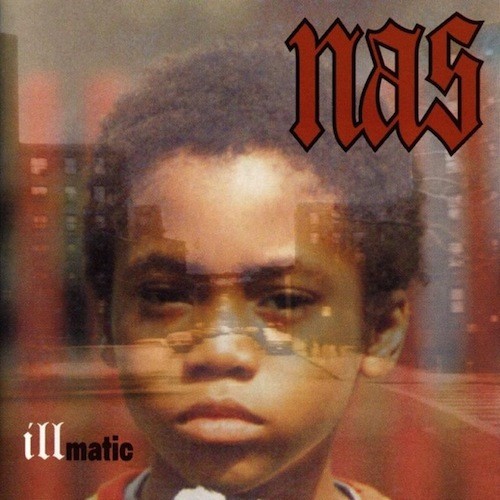

034 | Nas | Illmatic

[Columbia, 1994]

It’s somewhat baffling to consider that, upon its release, Illmatic was deemed something of a commercial failure, debuting on the Billboard 200 at 12, not going gold for two years, and not reaching platinum status until 2001. These sales numbers are somewhat shocking, especially considering how revered and influential the album ended up being. Despite those slow sales, though, like many albums on this list, audiences eventually found Nas’s masterpiece—justice. So what makes Illmatic so great? Well, allowing for its occasional homophobia (which I guess we do because of when the album was made), the album is a master class in old school rhymes and killer, stripped down beats. In essence, Illmatic is a meat and potatoes album, and became a strong foundation for hip hop’s future moving forward. But part of the charm of Illmatic is how unassuming it is—sure, it’s loaded with the expected posturing and what not, but it’s the easy charm and low key urgency of cuts like “Life’s a Bitch,” with its immortal chorus, or the slick, braggadocios mission statement of album closer “It Ain’t Hard to Tell” that makes the album pop so hard. While it’s the production and performances that ultimately make Illmatic timeless, we can’t forget how important the songs, themselves, are, here. Nas’s strengths as a writer rest in his timeless and honest examinations of hip hop culture and street life, always working towards a balance between thoughtful insight (“I sip the Dom P, watchin' Gandhi 'til I'm charged…”) to the basic desire to get paid (“I’m out for presidents to represent me”). Easily one of the most accomplished and influential hip hop albums of its era, Illmatic’s reputation deservedly persists. –James Brubaker

Also recommended: Big L, Lifestylez ov da Poor & Dangerous (1995), Jeru the Damaja The Sun Rises in the East (1994) and Wrath of the Math (1996), Mobb Deep The Infamous (1995), The Notorious B.I.G. Ready to Die (1994) and Life After Death (1997)

033 | Sunn O))) | Monoliths & Dimensions

[Southern Lord, 2009]

Sunn O))) is a metal act that literally tries to sound like metal–that is, metal being slowly pulverized into molten lava. Instead of adopting the prog-rock-influenced technicality of many of their peers, the duo (consisting of Greg Anderson and Stephen O’Malley) has surrendered itself to the drone. By adopting a minimalist approach, they have secured permanent residence outside the pop charts. But this is not a bad thing: Sunn O))), by embracing glacially paced metal, influenced by all sectors of the genre (including Norwegian death metal–notably through their frequent collaborations with Attila Csihar of the band Mayhem–dungeon synth, black metal, doom metal, and, of course, Black Sabbath), has created a sonic altar to the metal arts with their particularly textural and atmospheric brand of metal. Prior to the release of their masterpiece Monoliths & Dimensions in 2009, the most frequent criticism leveled against the group was that they had yet to shed the influence of the band Earth. Even a few years earlier, on their breakthrough album Black One (2005), the duo was still emulating the Dylan Carlson-led group. With Monoliths & Dimensions, Sunn O)))’s brand of art metal transcends these trappings and emerges as one of the most visceral yet arty creations of the last decade. The album consists of four lengthy songs, opening with “Aghartha.” The influence of Earth remains, but as the song sllllooowwwwlllllyyyy unfolds, tectonic textures emerge, including a percussive element that resembles a vampire scraping the inside of a coffin. Csihar’s oratory vocals come straight out of the cabinet of Dr. Caligari. “Big Church” moves further away from the Earth sound (though Dylan Carlson provides guitar work and vocal arrangements!), featuring a devastating, elliptical riff complemented by an eerie vocal choir. Texture is key here. Never have amplifiers sounded so crisp, guitar chords so percussive, as they do on this track. After a bit of a respite with the horn-tinged “Hunting & Gathering (Cydonia),” the album closes with a comparatively sunny (forgive the pun) sixteen-minute track, “Alice” (dedicated to Alice Coltrane). With this closing number, Sunn O))) realizes its potential. On it, they move away from the sizzling directness of power chords to harp-like arpeggios. The colorful track utilizes an atonal horn section, led by underrated jazz pioneer Julian Priester (seek out his amazing 1974 jazz fusion album Love, Love). With Monoliths & Dimensions, Sunn O))) have created an album that is as frightening as any metal album released. Despite the fright, it’s also one of metal’s most lovely, haunting, smart, and visceral epics. By embracing elements of modernist classical music and perfecting the recording process for their brand of sluggishly paced metal, they have created a work that is hard to beat. –Brian Flota

Also recommended: Earth Earth 2: Special Low Frequency Version (1993), Pentastar: In the Style of Demons (1996), Living in the Gleam of an Unsheathed Sword (2005), and The Bees Made Honey in the Lion’s Skull (2008), Nadja Truth Becomes Death (2005), Sunn O))) Black One (2005) and Domkirke (2008), Sunn O))) & Boris Altar (2006)

032 | Public Enemy | Fear of a Black Planet

[Def Jam, 1990]

Public Enemy’s second album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988), is regarded by many as the greatest hip-hop album ever made. (More on that later!) Following its release and the hype cycle it generated, PE were slowly building toward a third album that is, in some ways, even more revolutionary than its predecessor. It is also the type of record that could not be made today, due to its heavy reliance on samples, which the record industry cracked down on following the Grand Upright Music, Ltd v. Warner Bros. Records Inc. case in 1991, which ruled that Biz Markie used a sample from the crappy Gilbert O’Sullivan hit “Alone Again (Naturally)” without permission. Though Millions sampled plenty, the Beastie Boys upped the ante with their 1989 pot party platter Paul’s Boutique, which featured upwards of 200 samples. Not to be outdone, PE, with their production team The Bomb Squad, worked out a dense, apocalyptic, riotous aesthetic on Fear of a Black Planet that even today sounds ahead of its time. Expanding on the approach developed on Millions, The Bomb Squad increase the density of their samples and other sonic textures, creating a layered, kaleidoscopic call to arms. Following the dismissal of Professor Griff from the group for anti-Semitic comments made the previous year, Fear of a Black Planet finds PE in attack mode. “Brothers Gonna Work It Out,” which prominently features a sample from Prince and The Revolution’s “Let’s Go Crazy,” finds Chuck D delivering the thesis of the album: “History shouldn’t be a mystery / Our story’s real history / Not his story.” Themes of black empowerment through militancy, strength, spirituality, and education about and a resistance to white supremacy are found throughout the album, especially on rousing rave-ups such as “Welcome to the Terrordome,” “Power to the People,” “Revolutionary Generation,” “War at 33 1/3,” and, of course, the album’s biggest hit and most legendary cut, “Fight the Power.” PE mixes social commentary and a bit of levity on the Flavor Flav-led “911 is a Joke” (the other huge hit from this record), which offers an indictment on the slow response time to emergencies in black neighborhoods, and “Burn Hollywood Burn,” which points out the lack of African American actors and actresses in non-stereotypical roles in Hollywood-produced movies and television programs. Both critiques are, unfortunately, still relevant today. The title track addresses how white supremacist notions of racial purity negatively influence the perception of the children of biracial—black and white—parents. PE accomplishes this by including a sample from a standup performance by Dick Gregory. This dense album, which barely gives the listener time to breathe, features virtuoso performances from Chuck D, Terminator X, and The Bomb Squad. Together they made an important, and inimitable, album whose impact is still being felt today. –Brian Flota

Also Recommended: Cannibal Ox The Cold Vein (2001), El-P Fantastic Damage (2002) and I’ll Sleep When You’re Dead (2007), Makaveli The Don Killuminati: The Seven Day Theory (1996), 2Pac Me Against the World (1995)

031 | The Kniφe | Shaking the Habitual

[Rabid/Mute, 2013]

In 2006, The Knife became goth club legends with the triumphant release of their third proper studio album Silent Shout. The set of unsettling dance anthems raised their profile considerably. Though they kept themselves occupied with various projects over the next several years, they would not release a proper follow-up until seven years later. While Silent Shout consisted of unusual but tightly composed numbers, their follow-up, Shaking the Habitual, initially confounded some listeners with the inclusion of longer dark ambient material like “Old Dreams Waiting to Be Realized” and “Fracking Fluid Injection.” The duo of Karin Dreijer Andersson (Fever Ray) and Olof Dreijer again heavily distort their voices, transforming them into menacing, disorienting presences. On Shaking the Habitual, however, the group’s beats become increasingly polyrhythmic and disruptive, making this difficult, challenging music for a dance club setting. Furthermore, political themes are more explicit here with an emphasis on the harm caused by neoliberal economic policies. Let’s not forget the songs, some of which sizzle, especially the lead single “Full of Fire,” which at nine minutes in length never lets up its intensity for a second. “Without You My Life Would Be Boring,” “Raging Lung,” and “Networking” are similarly intense. Because of the length of the album (and the songs on it), Shaking the Habitual requires some heavy lifting on the part of listeners. Each track averages eight minutes in length, so even more accessible numbers like “Full of Fire” require patience. Repeated listens reveal a complex album that is a frightening look to the future (which is now) we have created, an Atwoodian future saturated with increased income inequality, melting glaciers, and tedious corporate synergies. On Shaking the Habitual, these realities have become the holy horrors, replacing the ghouls of goth’s past. –Brian Flota

Also recommended: Bat for Lashes Two Suns (2009), Fever Ray Fever Ray (2009), Fuck Buttons Street Horrrsing (2008) and Tarot Sport (2009), Gang Gang Dance God’s Money (2005), The Knife Silent Shout (2006)

100-86 | 85-71 | 70-61 | 60-51 | 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-21 | 20-11 | 11-2