And Never Climbs Back In by Kyle Hays

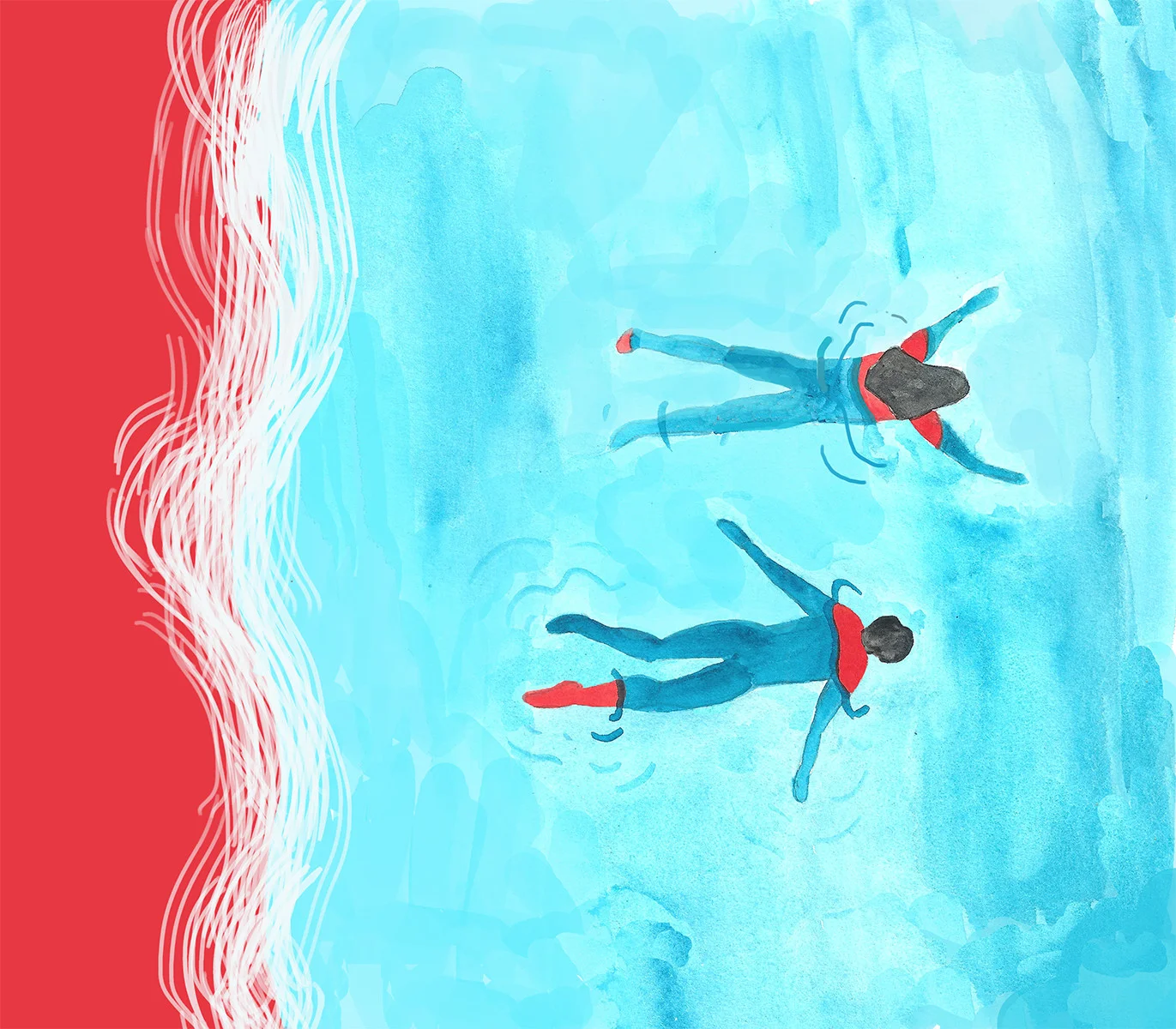

I tell her I can’t undo it for her, never could in this place, and just, for God’s sakes, come home, Jo Ellen. She stands at the edge of the lake and says nothing, helplessly looking at the small hole of water gone brown about itself. I know for sure this the last time I’ll come to her here. She turns her head and almost looks, looks the same blanked out way like she does following the small, clean rolling waves against the waterlogged pier where we are.

I say this place is no good for you anymore. I say this, almost whispering, but maybe it’s more to no one, no one in particular. There’s ache in me, ache that’s too tumbled over and too crooked to give to you. What’s left is grief. Grief burning myself and falling and narrowing to something I don’t know how to give, something I can’t pin down. I’ve given her all the grief she’s wanted, and all still falls short of our gone child drowned. What more can I say? I say Jo Ellen tell me what to say, tell me what to do, because I’ll do it, whatever you like, whatever gets you to come back. Everything we can salvage, with closeness or affection or falling back into life, is yours. There’s a home you call too small, but we can rearrange it, make it into something pretty and nice and grand.

Her clothes aren’t too clean. She has slept here on this pier, all night under the drench sound of water swept against wood. Morning light’s too much to bear around this water, and the air’s too cold to grasp anything for too long. She don’t look good, standing there like a house without no caretaker. She’s forcing me to limit myself, to reinvent what’s gone made me suffer.

I pull out some snuff, and give myself a lip.

Our life is a ghost or something else faded and blurred. I’ve lost her. She’s no more to me than he was no more to us. Standing there, spit dragging on to the wet brown water, I’m never coming back. I’ve still got time in me to give to someone else.

She holds out by her side the drawing he done for us when he was just a little thing. Done in crayon, the water and us and all smiles. Drew it a year ago, before he fell in and I took his room and emptied it back into boxes. Some of his stuff still gets dragged out, but everything will eventually be packed. I tell her there are things inside me I will let her keep, because I know there are things inside her too far gone to get.

Shallow, little water is still enough to drown. I tell her it was simply shallow, little water. What could we possibly do against shallow, little water?

She turns, looks, exhales, her breath the same color gray the dead can’t run away from. We both look long. She goes back away from me, and crumples the drawing into her pocket.

I can’t let her carry me down, but I’ve let her. I’m scared to be alone, and she knows I know she can’t ever let me leave. She brushes away the hair around her ears, and I understand she won’t ever come back from this because I won’t ever, truly, come back from this. I’m strong, but strong can’t function under so much ache.

She tells me to listen, to listen just under the sound of the waves. Hear him, Alan. Her voice is far and gone, tumbling in the movements under her breath. It is a voice tempered out of a raw hurt heart. We’re growing too damn small, I tell her. Every other day you want to go on and do something like this, and every time you make me come here, the ground gets lost beneath my feet. I tell her choose, choose right now because I’m never coming back. We can keep going, we can put all of each other into either tearing down the house or opening the door. It’s your choice.

Listen, she tells me, you can hear him, Alan. Would you be happy if I described all of what we hear as hard and wet. How can you say anything, about us, about coming home, if you won’t even listen?

She never speaks of sounds except when she’s here.

I look around and it’s early and the light washes out the sky, the lake, and other such things.

I tell her I’m here aren’t I? Drivin’ that long drive out to this place he loved so much. This the time I usually say to her there’s nothing more I can do. And I do say that and other things she refuses to hear. I say it again and again. Then I say I’m going to go and get the truck and when she’s done to come and--

She finally turns to me and says just listen and hooks her arm around mine. She asks for this one time to listen, to really listen close because he’s in everything. She’s whispering now, saying how sorry she is and that when the heart gives, nothing else can make it give again: it just falls out of your chest and never climbs back in. So tell me, Alan, she says, how can say you don’t hear nothing when he’s so clearly there?

Drafts of air swim around us. All sounds here come back to that broke blue lake. There’s the thudded knock of a boat thrown about inside its dock, a thrashing hum of a hummingbird left slicing through the cold, and the still water carrying sound eager to be solved in the style of mysteries. There’s no more of him in sound than there was of warmth between us. I hear traffic noise too far off to make a difference. A fish works small under a stray patch of ice, roiling brown dirt below the surface. Down the beach, a dog digs in the sand and looks his head up, standing quietly, as if he were placing all his desires and needs around that morning air, and begun to begin his endless ritual of never standing still for too long and put his paws in motion back down towards the earth in a spot he won’t remember tomorrow.

...

Kyle Hays is currently pursuing an MFA at Oklahoma State University. His writing has been featured in The Seattle Review and is forthcoming in The Potomac Review.