Science Rules: Brad Efford on Bill Nye the Science Guy, Episode 5: "Buoyancy"

I.

The wet sub most closely resembles a plastic bath toy: bright yellow and fish-shaped, a tiny propeller bolted onto its back. You can imagine a tub-wrinkled toddler's hand gripping it from above, pushing it through the water. The toddler makes an airplane noise because for her this is the noise of all machinery.

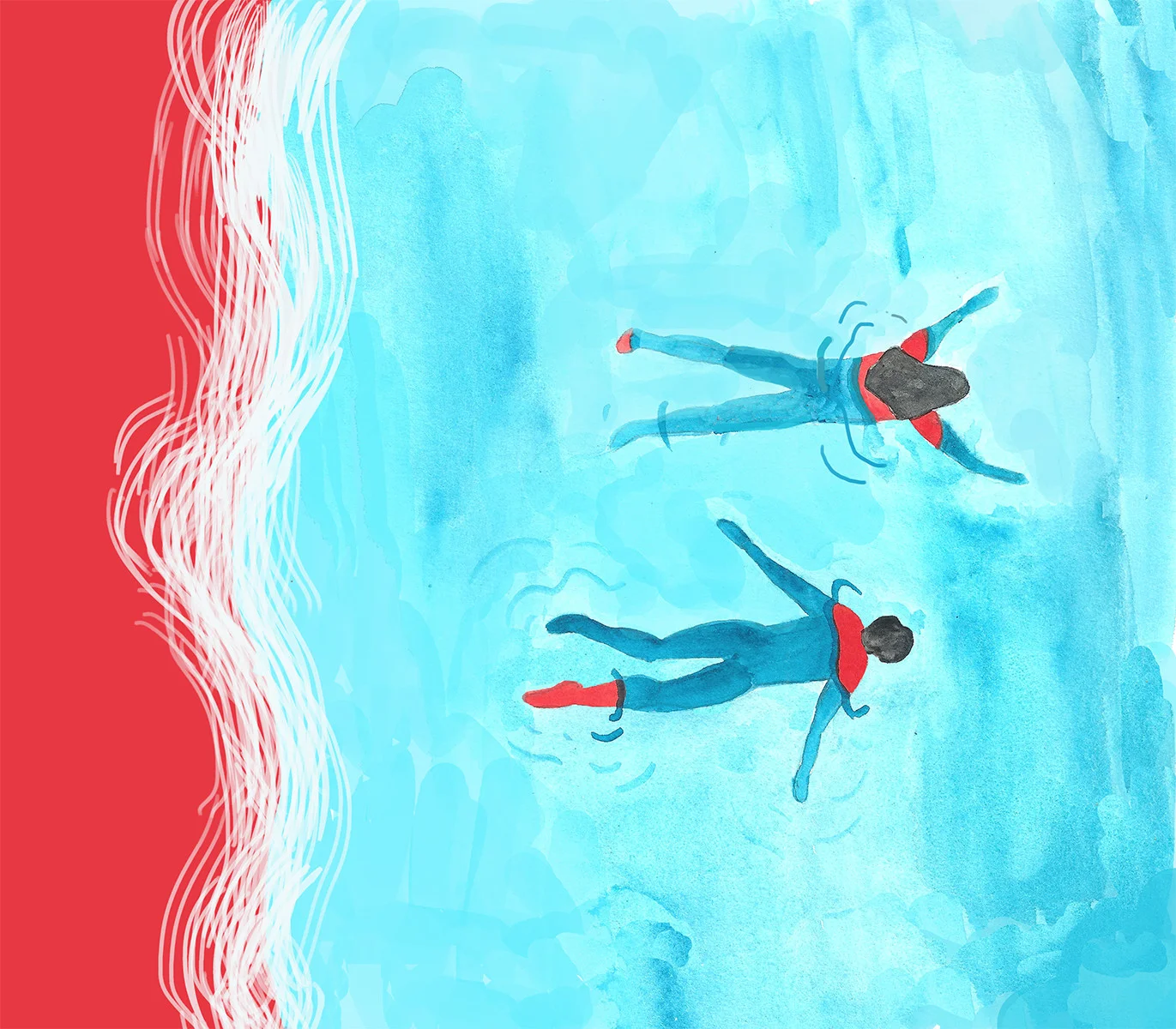

But if the wet sub is a toy, it is the world’s most terrifying. Two divers fit inside, only barely. Its movements are people-powered, driven with pedals attached directly to the tiny propeller from inside. To pedal, one diver sits facing the sub’s dark ass, their back to the front window. The only window. They operate blindly, fit into a steel lipstick tube and tossed into deep water. The second diver lies face-down in the window, a low-crawling soldier, to navigate depth and direction. Nothing better embodies sardines, their airless tin can.

To the divers, wet sub operation must seem, more than anything else, like a marriage. Tight quarters, constant reliance, blind faith, buoyancy control. To keep from sinking you must keep moving. To stay afloat, depend on your pedaling partner. Half control, half total-lack-of. Breathing in, breathing out. Trusting that the distanced dark water will reveal itself to be nothing more than waiting only for you to reach it.

II.

If you can displace enough air, you’ll go up, the science guy promises. Just like a bubble in water.

The science guy is taking off in a hot air balloon, a comical machine made only more comical by its carriage made of woven basket. Nothing about the hot air balloon seems logical, safe, or okay. When the science guy shows you a desert scene capped by a skyful of multicolored, spinning balloons, he means for it to amaze, to elucidate great beauty. But the balloons are too high, kept a million miles above the ground only by buoyancy’s invisible hand. Even the science guy admits it: all they’re doing is floating. Going up. Fabric bubbles in water made of air.

To trust in hot air balloons, you must trust first in science. And herein lies the rub. Science is invisible, simply a collection of concepts that keep days operational. Above all, and before anything else, you must buy into it. Invest in your own blind faith, and hope you float.

III.

When you place an object in water—boat, daughter, ice cube—the weight of the object is displaced. Pushed out and around. Dis-place, place away, you with me? the science guy asks. He demonstrates the concept, lowers a model boat into a tank and measures the water lost: it is the same weight as the boat. If anything, the science guy is proving that there is no difference between objects other than what they weigh. They’ll displace water no matter what. The job’s the same regardless.

Freud once said something similar, but he was Freud. His displacement was about sex. Just another defense system for the ego: taking out frustrations on unrelated, unguilty objects. And for Freud, the only frustrations were sexual frustrations. But the job’s the same regardless: place away the weight of anger equal to the heft of its source. It’s a fancy way of saying blame. An old-fashioned way of turning down the volume on your own imperfect image. The model boat of science as just another metaphor for understanding love, and dealing swiftly with it. For better or for worse.

IV.

Stay buoyant! the science guy implores. He is in a car which is a boat which is in a body of water off the coast of California. The advice is easy enough for him to give.

In truth, staying buoyant’s demanding. Sinking and floating both depend on trust. The coupling of your own fear of water with your own fear of darkness with your own fear of stopping breathing. A veritable marriage of undesired instinct. The science guy ties a balloon to a stone, drops it in a tank: neutral buoyancy allows for the pairing to hover mid-water. Neither totally sinking nor all-the-way floating. It’s how scuba divers and fish work, the science guy explains, then splashes water from the tank in giddy playfulness.

Where is trust in this neutrality? Does it multiply or lessen? The balloon and the stone complicate the process—that much is certain. They are, like most misunderstood science, a poor metaphor for love. At best, a way to wrestle with two people sardine-tinned and half-blind by self-volition. Each trusting in the other to sink them, to help them float.

...

Brad Efford is the founding editor of The RS 500, a project pairing each of Rolling Stone‘s 500 Greatest Albums of All Time with an original piece of writing. His writing can be found in Puerto del Sol, Pank, Hobart, and elsewhere. He teaches English and history in Austin, TX.

Original Artwork by Lena Moses Schmitt.