U.S. Girls and Springsteen: Dark Mirrors of Pop Music by Eric Wallgren

When I first heard U.S. Girls’ debut album, Introducing..., I thought it sounded like music itself had been turned inside out. It seemed to be coming from a place so isolated that hearing it made me feel deeply and profoundly connected to its creator. For a while I felt like I, and I alone, understood what this record was supposed to be. But then I went online and found that at least a few other people had experiences with it that were near identical to mine. And I discovered that the isolated space that U.S. Girls dug into was much more shared than I had realized. Introducing... is music at its most primal: rhythmic as opposed to melodic, chanted as opposed to sung, and generated by impulse as opposed to design. Many would say that—in the avant-garde tradition of John Cage, Yoko Ono, and Brian Eno—it’s not even music, and while that’s a legitimate way to understand what Remy was doing early on, it misses the point: which is that U.S. Girls was a pop project from the very beginning. The early work is flattened and distorted; it challenges its audience to listen from different angles than they’re probably used to, but this music is guided by the time-tested pop ethos of tight structure and emotional directness. Remy’s lyrics are simple and repeated into the ground on “Don’t Understand That Man” (“but don’t you understand / you had it all with me?”) and “Outta State.” (“you’re gonna run, you’re gonna run run / back back back back where you came from”) They’re sung with an almost possessed urgency, in quick songs that make abrupt maneuvers before the impact of any one idea has the chance to wear thin.

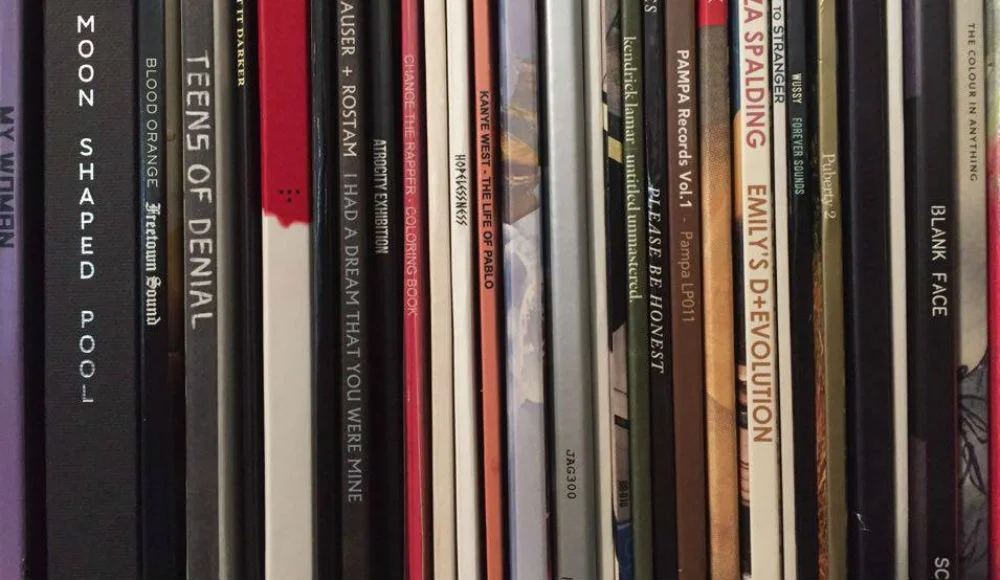

Fast forward to last year’s Half Free and you hear a new U.S. Girls that works according to the same impulses but shakes off the grating, otherworldly atmosphere to make a record that “sounds pop” without any effort on the listener’s part. The hooks are straightforward; the melodies stick well after the songs are over; and the beats stomp heavy like a heartbeat. If this sounds like a sell out or a compromise, it’s not. The ideas behind Introducing... are still there on Half Free, but they’re expressed more clearly, if less dramatically, with Half Free’s more accessible sound. And as a way to understand this transition, I’m going to look at it through the context of a similar transition made by Remy’s idol: Bruce Springsteen.

***

In 1982, Springsteen released Nebraska: a record that, though different in a lot of ways, has a similar atmosphere to Introducing…, and gives off a lot of the same feelings. Recorded alone on a four-track recorder with no percussion and some light overdubs, Nebraska is a sparse record that feels isolated. And the songs tell stories that are dreary to match. Nearly half of them end with murder or execution. Nearly all of them are about people at the end of their rope, turning to or contemplating a life of crime, or coldly accepting the deadening monotony of blue-collar life. But the song that truly reaches the cerebral vulnerability of Introducing… is “My Father’s House.” In it, the narrator has a dream in which he’s a child, lost in a dark forest until he sees the light of his father’s house. So he runs, and: “The branches and brambles tore [his] clothes and scratched [his] arms / but [he] ran till [he] fell shaking in his arms.” The narrator then wakes up and decides to drive to the father’s house of his dream, to ominously find out from a neighbor that his father no longer lives there.

Of Nebraska, Springsteen said once in an interview with Rolling Stone: “I was renting a house on this reservoir, and I didn't go out much, and for some reason I just started to write.” Remy’s earliest work as U.S. Girls was born out of a similar isolation. She has said she started recording music as a way to close herself off from someone she was dating at the time. If those works are the singular visions of artists who were closing themselves off, then the progression to Springsteen’s next album, Born In the U.S.A., and U.S. Girls progression from Introducing… to Half Free open those visions up for a larger audience. Springsteen has said that to him the songs on Born in the U.S.A. are mostly the same as the songs on Nebraska: stories of people up against the dark realities of American life. And in fact, four songs on Born in the U.S.A. originally came from the Nebraska sessions. What’s obviously different, though, is that the songs were recorded with a full band, are stadium-ready huge, and wound up stitching together a blockbuster of an album, spawning 7 top 10 singles and, to date, selling over 30 million copies.

Half Free is obviously not that type of commercial gigant. But in relative terms, it was a knock out of the park for U.S. Girls. It was released on what could be considered a “major” indie label (4AD); it got generally good reviews from publications that wouldn’t even acknowledge U.S. Girls around the time of Introducing..., and, most importantly, it reached a wider audience that’s basically inaccessible for the kind of fringe artist that U.S. Girls was several years ago. But Remy takes these opportunities and uses them to tell stories of trialed women that might be difficult for her new audiences to swallow. On “Damn That Valley,” a widow mourns the loss of her husband to war. On “Woman’s Work,” a woman tries to use plastic surgery as a way to confront her own mortality. Lives are torn apart by men or by society on multiple tracks. “New Age Thriller” closes with these lines repeated: “you all have nothing here / you have so much to fear,” and this is the certain feeling of doom that sheens the entire record.

In an interview with Impose last year, Remy said, referring to Bruce Springsteen: “He’s done this for a long time, trying to shine a light on the average person. And talk to them, about them. I liked that. But he doesn’t really have that many songs from a female perspective. No one’s ever really done that. So I just wanted to do that.” Springsteen’s commitment to telling the stories of blue-collar “average” people is an integral part of his legend, but Remy is right; his focus is heavy on male perspectives. Looking just at the track list for Born In the U.S.A., I see the story of a Vietnam vet who struggles to find any support in his home country (“Born in the U.S.A.”), a highway worker who’s sent to jail after he skips town with his young girlfriend (“Working on the Highway”), a frustrated guy who feels stuck in his life working a graveyard shift (“Dancing in the Dark”), and a handful of other similar stories.

I don’t know that if Springsteen wrote more songs about women, anybody would even want to hear them. There are plenty of women who can speak on those experiences better, and, like most storytellers, he’s at his best when he writes characters he can see himself in. Same goes for Remy, and that’s why she told the stories she did on Half Free.

What Remy and Springsteen create—from their respective viewpoints of the world—are songs in which circumstance actually matters. People in their songs don’t just fall in love; they fall in love because they’re broke, humiliated, and feeling at the end of their rope, looking at the escape they could make with someone else. People in their songs don’t just have dreams; they have dreams that might be impossible and the songs are sure to follow through with the heartbreak and punishment they will have to endure for dreaming them. They’re dark mirrors of pop’s insular universe, where emotions can be felt and expressed free of consequence. These songs burn with the desire to reach a better a place, and the fear of knowing it may never happen.

***

“Prove It All Night,” off of 1978’s Darkness on the Edge of Town, is exactly this type of song. In it, Springsteen sings: “You hear their voices telling you not to go / they’ve made their choices and they’ll never know / what it means to steal, to cheat, to lie / what it means to live and die.” On an album built around a concept of the darkness on the edge of town, “Prove It All Night” is a bold invitation to discover what’s in the mystery that lies outside of misery or, in real terms, the world that lies outside the narrator’s small, suffocating community. He doesn’t pretend to know what’s out there, but he wants to break free so badly that he’s willing to push all risks aside and find out.

But there’s another version of that song: the U.S. Girls cover that appears on Introducing…. Performed with a single drum and no other instrumentation, Remy sounds perfectly hopeless when she deadpans: “Everybody’s got a hunger / a hunger they can’t resist / There’s so much that you want / you deserve much more than this,” a line that Springsteen, in his original, sung with guttural and declarative faith. From his character’s desperation springs reckless courage. From U.S. Girls’, there’s only desperation. Remy sings like a person who feels utterly trapped and too hurt to dream of anything different.

It’s a very good cover, and U.S. Girls has made a lot of those in the past few years, but there’s one cover she did that I like even better.

I remember finally going to see U.S. Girls live in 2011, and walking in during her performance to a song I thought I recognized and thought “there’s no way she’s covering ‘The Boy is Mine’ by Brandy and Monica right now.” Then, a few months later, U.S. Girls on Kraak came out and sure enough, “The Boy is Mine” was on it. What I love about the U.S. Girls’ version is that it writhes, screams, and generally unfurls the coyness and bravado of the original: in which Brandy and Monica sing like they don’t see a threat in one another, like they can brush each other off and their rivalry is trivial. But that’s not how Remy sings it. For her, there are stakes. The boy she’s singing about matters to her and she’s afraid of what might happen if she loses him to somebody else.

Her version affectionately rips open the original. It’s like what she does to pop music in general: finds the animosity and fear that always seethes under any smooth surface—and unleashes it.

...

Eric Wallgren lives in Chicago, where he plays in a band called Lamestains. He's online at ericwallgren.tumblr.com.