Science Rules: Brad Efford on Bill Nye the Science Guy, Episode 20: "Eyeballs"

I.

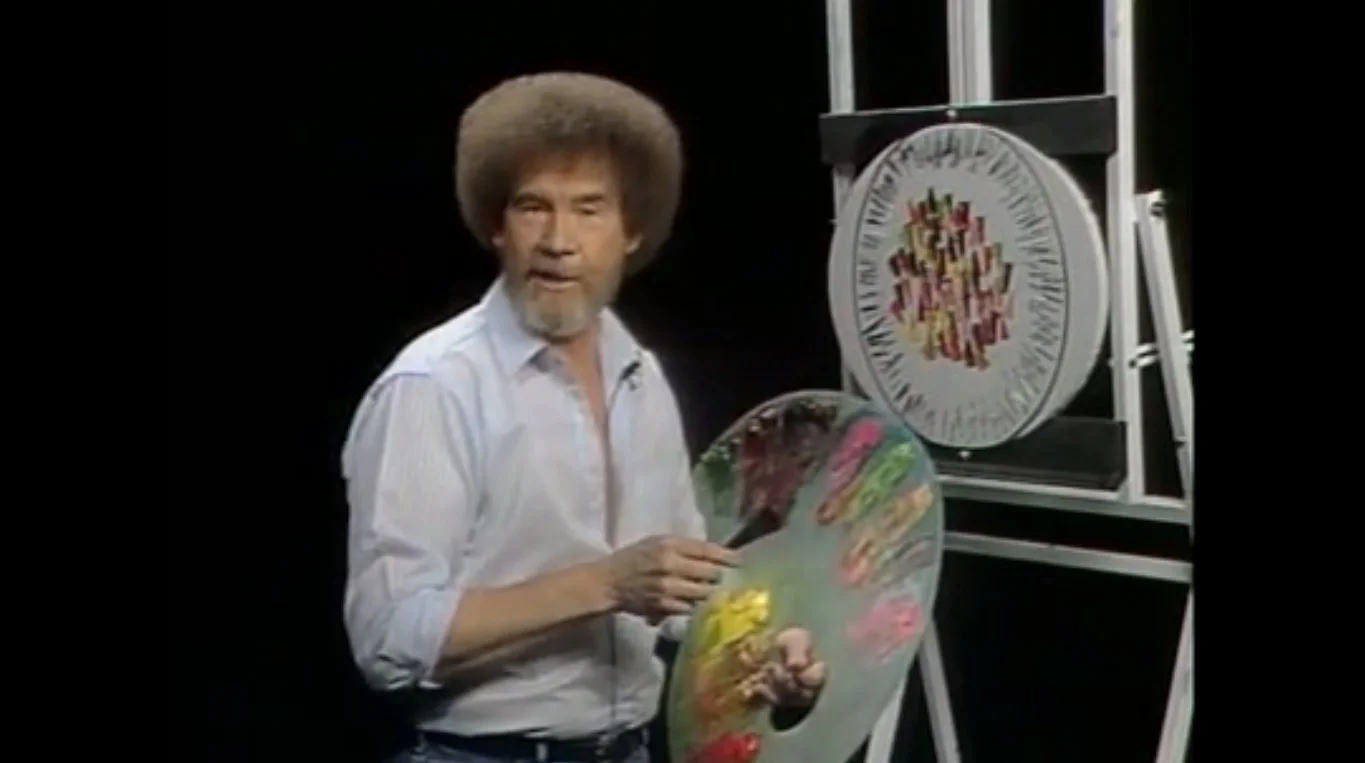

And here we are at the retina, land of happy little rods and cones, Bob Ross says. He gestures to the canvas shaped like a circle with an oval drawn across it.

Did you know that everything you see is an image on your retina? asks Bob Ross. It’s true. And those images are made by two kinds of cells called rods and cones.

Let’s paint some happy rods around the edge.

In quick, rhythmic strokes, he outlines the oval in black triangular dabs. It is as his faithful say: meditative, soothing, hypnotic. Later, he returns to fill in the oval with cones, more daggers of paint, this time in an array of muted colors. The science guy has asked Bob Ross to diagram the eyeball, to teach you and all the rest of the watching world how the thing actually works. Bob is an easy someone to pick for this job—he is a natural teacher. Patient and careful and funny in an odd, off-kilter way. You don’t know if he’s in on the joke—whatever the joke may be—but you also don’t think he’d mind much either way. There is much to be admired about Bob Ross. Within a year and a half, he will be dead.

II.

As a 15 year old trying his best to survive both adolescence and the weirdness of a post-boom-and-collapse, pre-Disney Orlando, Bob Ross threw in the towel. He decided he would be better suited learning carpentry and making a living working alongside his father. His mother and father, Ollie and Jack, were just recently back together after having been married, separated, married to different spouses, separated from those spouses, and remarried to one another. They were growing frustrated with how many times they’d come home over the years—both separately and together—to find some different injured animal taking up residency in their home while Bob nursed it back to health. The most oft-repeated of these is the case of the bandaged alligator in the bathtub. Bob needed direction; carpentry would do, for now.

Three years later, Bob was still playing Dr. Doolittle and had lost the tip of his left index finger to a backsaw. As a painter, he’d learn to disguise this loss with the palette, thankful for the cover it allowed. For now, he was 18, still in Orlando, still happy enough, but rutted. He enlisted in the U.S. Air Force and was promptly reassigned to Alaska. Whether it was the new environment, the rigor of the post, or the complete upturning of his day-to-day, who can say: almost immediately, everything changed for Bob Ross.

III.

There is an epileptic squirrel in Bob Ross’s jacuzzi. He brings Linda Shrieves from the Orlando Sentinel out back to show her. The jacuzzi’s half-closed on top, and when Ross lifts the lid the rest of the way, Linda peers down: yup, there it is. The squirrel’s cage is clean and takes up nearly half of the space—the squirrel itself is alert, planted on all fours, staring straight up at the looming humans above, tail twitching.

He’s getting better, Bob Ross says. Slowly but surely, he’s getting better.

They watch a little longer but there’s not too much to see; the squirrel’s epilepsy is, of course, not constantly apparent. Past the deck, in the long backyard, there are more large cages, some covered with heavy blankets for warmth or to block out light. Ross takes her to see the crow with the smashed left wing, who caws horribly when they uncover her bars. Linda briefly marvels at the care clearly taken on its bandages. There are more squirrels—one with no tail—a fox with an eye patch, a raccoon who, Ross says, is recovering from having a bone dislodged from his throat. His love for each of them is evident, the close attention paid to their individual needs immediately apparent.

This is both nothing like and exactly to a T what Linda was expecting when she took this assignment. Bob Ross is not much different than how he appears on television—same supernaturally calm demeanor, same bright impossible eyes, same afro—he just contains more multitudes. He’s somehow a richer version of his TV self, somehow more full, deeper. If anything, Bob Ross doesn’t play a role for the cameras: he just tones it down.

Back inside the house, he offers her a glass of water and says, The majority of our audience does not paint, has no desire to paint, will never paint. They watch it strictly for entertainment value or for relaxation.

We've gotten letters from people who say they sleep better when the show is on, he says and smiles, nonplussed. It suddenly becomes apparent to Linda that she might have met the happiest person in show business. Bob Ross travels to Muncie, Indiana every three months to tape new seasons of The Joy Painting. He and the crew finish all thirteen episodes in just two and a half days, and then he flies back home. He makes little to no money from the show, as it goes with most PBS series, but a small fortune from his brand. Bob Ross painting classes on VHS. Bob Ross canvases. Bob Ross brushes and palettes and paints.

Everyone has their problems, but Linda can’t shake the feeling that the man before her sipping hot water from a plain white mug and waiting patiently for the next question is really doing things right. He seems like he’d be content doing whatever. But he’s not doing whatever. He’s settling further and further into a dream.

IV.

The barracks door swings shut behind him as the ranks fall in for inspection. First Sergeant Ross walks slowly from bedpost to bedpost, barking revisions peppered with insults. Unspecific and subtly lackluster, the invectives come from obligation more than anything else. Maggot and shit stain and worthless this and that—almost straight out of a movie. The newbies still pop to it, but there are guys in here who’ve known this man for months now, and they can tell. They would never show they can, but they can.

Nights, First Sergeant Ross goes for walks around the base to clear his head. It’s been nearly 20 years since he joined up—he’s almost 40 now, and feels it. Eielson Air Force Base is wide open, like you see in the movies, lined with jets and beige buildings. Only difference is Eielson’s in Alaska, 25 miles southeast of Fairbanks, which means mountains, and big fuckers, too. Snow-capped and ragged like in a painting. An apt simile, of course. First Sergeant Ross paints two or three landscapes most days during lunch, sandwich in hand. Has for years now. Give them away to whoever shows an interest or paints over them and starts all over again. Then at night he walks. The lights in Eielson are always on, for obvious reasons, but he’s found corners dark enough where if he waits and keeps gazing, his eyes will adjust.

He can practically feel the rods and the cones shifting in his retinas as the stars reveal themselves to him. He is amazed how there is nothing above him, then suddenly something. Everything. Every light a history. He knows he is on a course and that course is shifting. He has no clue the direction. He thinks when he retires he might grow out his hair.

This piece is indebted to Linda Shrieves’s 1990 interview with Bob Ross for The Orlando Sentinel.

...

Brad Efford is the founding editor of The RS 500, a project pairing each of Rolling Stone‘s 500 Greatest Albums of All Time with an original piece of writing. His writing can be found in Puerto del Sol, Pank, Hobart, and elsewhere. He teaches English and history in Austin, TX.