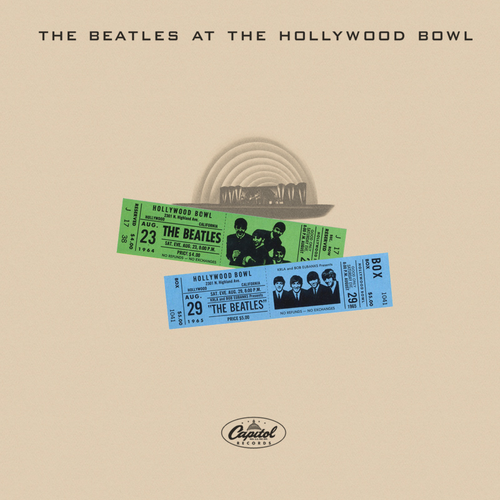

Until September 8th, 2016, The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl—a 1977 live album culling performances from the Fab Four's 1964 and 1965 performances at the famous Southern California venue—was the last piece of Parlophone/Capitol Beatles product to escape digitization (save for the lousy collection of Christmas Fan Club records the group released from 1963 to 1969). Newly reissued with four previously unreleased songs to help promote the Ron Howard concert documentary The Beatles: Eight Days a Week: The Touring Years, the album, renamed Live at the Hollywood Bowl, is reborn thanks to better source tapes and superior contemporary recording technology. Unlike the two Live at the BBC compilations (released in 1994 and 2013)—which both consist of live-in-the-studio performances—Live at the Hollywood Bowl stands as the one live concert recording the group approved for release. This fact alone gives the album importance in their discography. However, even after listening to the newly remastered and expanded version of the album, one can understand why it took nearly 35 years from the advent of the compact disc for the LP to get an official digital release.

Until September 8th, 2016, The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl—a 1977 live album culling performances from the Fab Four's 1964 and 1965 performances at the famous Southern California venue—was the last piece of Parlophone/Capitol Beatles product to escape digitization (save for the lousy collection of Christmas Fan Club records the group released from 1963 to 1969). Newly reissued with four previously unreleased songs to help promote the Ron Howard concert documentary The Beatles: Eight Days a Week: The Touring Years, the album, renamed Live at the Hollywood Bowl, is reborn thanks to better source tapes and superior contemporary recording technology. Unlike the two Live at the BBC compilations (released in 1994 and 2013)—which both consist of live-in-the-studio performances—Live at the Hollywood Bowl stands as the one live concert recording the group approved for release. This fact alone gives the album importance in their discography. However, even after listening to the newly remastered and expanded version of the album, one can understand why it took nearly 35 years from the advent of the compact disc for the LP to get an official digital release.

When Parlophone and Capitol Records recorded the shows (August 23, 1964 and August 29-30, 1965) from which the songs on this album were culled, the intent was to release a concert album. After three shows worth of material, the project was rejected mainly because of the crowd noise. In fact, the roaring audience might be the most impressive and resonant feature of this album. The fans in the Hollywood Bowl on those nights—some 17,500 raging Beatlemaniacs—create a noise on par with 20 fighter jets flying at top speed some 7 feet from your eardrums that runs over, across, and beyond every single note The Beatles play. The shows were produced for release by Voyle Gilmore, who is the producer most known for his work on many of Frank Sinatra's great 1950s albums for Capitol Records. Clearly The Beatles, and their fanbase, were a different beast from the cool, restrained sound he helped tailor for Sinatra.

If one were to describe this meeting between The Beatles and their fans as a battle, the fans clearly win. There are several reasons for this. The most important being that at the time, live concert equipment was a far cry from what it is today. For instance, there were no monitors. As a result, The Beatles could never really hear themselves playing. It wasn't until about five years later that the quality and design of the equipment caught up with the times. (See the classic Rolling Stones 1970 documentary Gimme Shelter to see the roots of how rock bands sound live today.) Given these challenges, The Beatles perform well. Imagine performing a concert in which you could barely hear yourself play. It probably wouldn't go as well as this one.

On this re-issue, the crowd noise is somewhat subdued compared to the 1977 release. As a result, we get a better sense of how The Beatles handled their singular concert experiences. Essentially they blast through their sets, high on pure adrenaline. The tempos of their songs are increased exponentially. By the time of the 1965 shows, the group had effectively been a major label act for less than three years. Because of this, they tend to stick with their hits ("Ticket to Ride," "Can't Buy Me Love," "Help," "A Hard Day's Night," "She Loves You"). A few B-sides and album cuts are thrown in to satisfy their most hardcore fans ("She's a Woman," "Dizzy Miss Lizzy," "Boys" [with Ringo Starr on lead vocals], and "Roll Over Beethoven" [with George Harrison singing]).

Because The Beatles were nothing more than a straight-up pop band at this point, Live at the Hollywood Bowl ends up being moderately underwhelming. Their live arrangements hardly vary from the studio versions. At the time, though, that's what concert attendees demanded. On these terms, the shows are a success. The Fabs are pretty tight musically, making a few flubs here and there, which is understandable given the sheer force of the crowd's screams. The one area in which they struggle throughout the set is their vocals. It is hard for them to approximate the harmonies found on their records. On "A Hard Day's Night," John Lennon's lead vocals are quite flat.

While the album offers very little new musical "information" about The Beatles, it possesses a few rip-roaring renditions. "Boys," which was always a Beatles barnburner, is one of the highlights as the crowd loses their shit when Ringo is introduced. "Long Tall Sally," their great Little Richard cover, features the group in peak form, bolstered by Paul McCartney's best Little Richard imitation and George Harrison's finest moment as a lead guitarist during the earliest throes of Beatlemania. The Lennon-McCartney originals are highlighted by a driving performance of the introspective Lennon rockers "Help" and "All My Loving," which is given more precision here than the version heard on the legendary Ed Sullivan Show performance of February 9, 1964, when they were clearly overwhelmed by their audience of rabid, new American fans. (This performance is captured on the 1995 release The Beatles Anthology 1.) The four newly released tracks ("You Can't Do That," "I Want to Hold Your Hand," Carl Perkins' "Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby," and their country-tinged "Baby's in Black") are highlighted by "You Can't Do That," which is perhaps the one track on the album that rivals the quality of the studio version (found the 1964 album A Hard Day's Night).

The Beatles' other widely circulated show, the semi-official bootleg most famously known as Live! At the Star-Club in Hamburg, 1962 (which, like The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl, was first released in 1977), might be worth seeking out for fans of the group interested in hearing what the group sounded like live in a much smaller venue. Though notoriously lo-fi, the recordings, believed to be culled from shows between the release of the group's first ("Love Me Do") and second ("From Me to You") singles in late December, 1962, show just how energetic, jovial, and witty the group could be. The reason these recordings remain unsatisfactory is that they mainly consist of cover songs, many of which are far weaker in quality than the songs John Lennon and Paul McCartney (and, later, George Harrison) would eventually write. Because their last huge venue concert was performed on September 29, 1966 at San Francisco's Candlestick Park, they weren't performing live for nearly half of their time as international superstars. This makes the reissue of Live at the Hollywood Bowl particularly valuable to amateur and professional music historians, even if the album ends up being more valuable than it is necessarily great.

Ultimately, the re-release of Live at the Hollywood Bowl is going to be more exciting to hardcore Beatles fans than your average fan of rock music. Unlike the The Beatles Anthology series and the first Live at the BBC set, which featured plenty of exciting revelations, Live at the Hollywood Bowl gives us slightly lesser versions of songs we know and love, drenched with an insane amount of crowd noise. That crowd noise is probably the reason to listen to the album though. Despite being the most popular band in the world by a long shot, The Beatles faced what would be insurmountable odds for most other acts, being one of the first rock acts to play shows at huge venues with subpar sound equipment. Considering the circumstances, they perform admirably here. The album provides ample audio insight into the deafening roar of Beatlemania at its peak.

...

Brian Flota is a Librarian who lives in Harrisonburg, Virginia. He co-edited The Politics of Post-9/11 Music with Joseph P. Fisher in 2011 (Ashgate). He also contributes reviews to Library Journal and The Hairsplitter. When he was a three-year-old, his favorite song was “Copacabana (At the Copa)” by Barry Manilow.