Science Rules: Brad Efford on Bill Nye the Science Guy, Episode 11: "The Moon"

I.

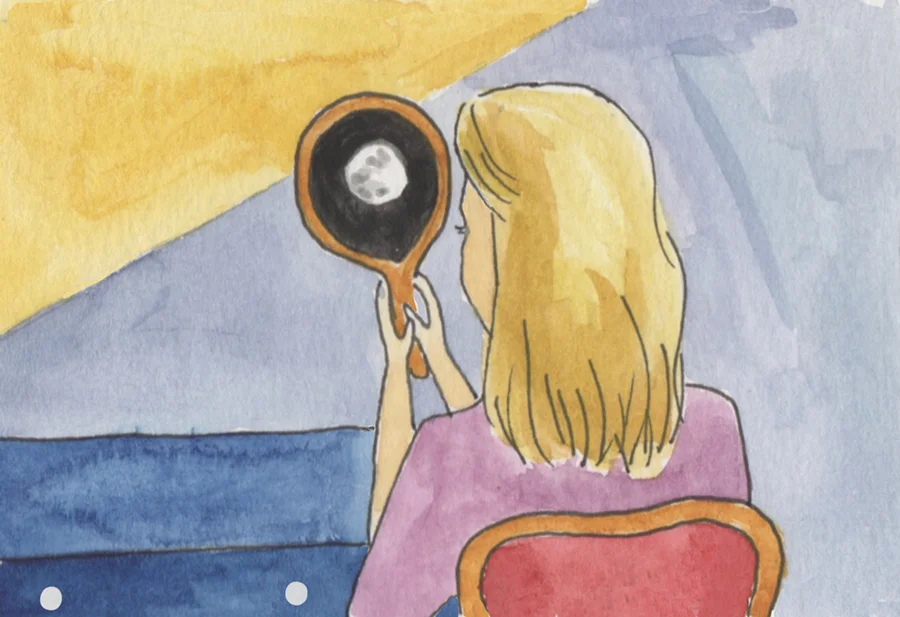

Moonglow is really sunglow reflecting off of moon rocks, the science guy says. He holds a globe-sized moon in his right hand, extended away from his body, a small mirror in his left. He jiggers the mirror so that it catches the lab’s bright lights and throws them over the moon like laundry snapping in the wind.

The science guy explains why the makeup of moon rocks and those on Earth is so similar: Perhaps the Earth was hit by a giant meteorite—a giant rock in space. It hit the Earth, and that material spun off and formed the moon. He takes his meteorite model and smushes it slowly and dramatically into his model of the Earth, making the kshhhh noises children make when colliding action figures. He pulls the moon away, taking with it its light, our tides, billions of years of dreams and serenades.

II.

The specifics behind the car wreck that ended Doris Day’s dancing career and shoved her into singing are impossible to pin down. Some sources describe “an accident involving a train,” others don’t mention a train at all, and the local paper headline from the week after states only “Trenton Friends Regret Injury to Girl Dancer,” a menacing, off-kilter angle from which to report the story. If a train, then what friends? If friends, what train? It’s not impossible to piece together assumptions, but the assumptions aren’t exactly comfortable, either. The news story behind the headline seems lost to history—it surely would shed light into every shadowed corner.

Here’s what is known: on October 13, 1937, Doris Day’s right leg was shattered in a car accident. She was either 15 or 13 years old—why is nothing certain in the life of Doris Day?—and had been preparing a move with her dancing partner, Jerry Doherty, from small-town Ohio out to Hollywood to make it big time. Her mother had already shipped the majority of their belongings—it was a done deal. The accident must have been cataclysmic, then, not only physically but from just about every other angle you can imagine, as well. During her planned 14-month recovery, Doris Day fell and reinjured her legs. She was young, bedridden, depressed. She turned to what anyone would, to what everyone turns every day: her radio.

“There was a quality to her voice that fascinated me, and I’d sing along with her, trying to catch the subtle ways she shaded her voice, the casual yet clean way she sang the words.” This is Doris Day, reflecting later on the voice that would become her inspiration, aspiration, and ticket out of town. That voice, of course, was Ella’s. Who else could it have been? The moon doesn’t know it is the moon—all it sees is the Earth around which it revolves. Ella is not the moon in this analogy.

Doris Day took singing lessons—her vocal coach purportedly charging her for only one out of every three, so encouraged was she by the talent, the prospect, the potential—and by 1945 had scored her first bona fide hit with “Sentimental Journey.” She was either 23 or 21 years old, had a three-year-old son, and was making do in Ohio, preparing to embark on her first cross-country tour, preparing, finally, to make it to Hollywood, where she would make it beyond, go orbital, break from the Midwest like a plaster cast whose purpose has been met.

In 1957, Doris Day recorded Hudson, Mills, and DeLange’s “Moonglow.” By then, she was The Doris Day: a figure as much as a name, a screen star as much as a singer, an irrepressible force having nearly lived already through her prime. The song itself is as standard as standards come. Her version glows absolute, iridescent, the phrasing patient and anticipatory, her voice fluttering like gossamer wings in the upper register, slinking like a hunting tiger in the lower. You can hear the confidence of someone who’s achieved everything she’s ever wanted. You can hear the light reflecting off Ella, the light which is really a torch, the torch burning softly, proudly in Doris Day. She sings as though she knows already, before the scientists have figured it out: moonglow’s only a reflection of itself, shining brighter the nearer it edges to its source.

III.

Ancient Greek astronomers learned the Earth was round the moment they saw its shadow cast on the moon. The science guy is demonstrating this with a bright light and his models of the Earth, the moon, the sun. He shows the way shadows take the form of their sources, the bodies that give them life. The Earth is round, so when the moon passes behind it, the light disappears in a slowly forming curve. The body itself doesn’t go anywhere—eventually, if it keeps moving, it will reemerge into the light, discover its own form without inspiration. That moonglow gave me you. Eventually the body will find its shadow again, then break it as it moves. The cycle is both brutal and beautiful: full life, waning life, new. That moonglow gave me you.

...

Brad Efford is the founding editor of The RS 500, a project pairing each of Rolling Stone‘s 500 Greatest Albums of All Time with an original piece of writing. His writing can be found in Puerto del Sol, Pank, Hobart, and elsewhere. He teaches English and history in Austin, TX.

Original artwork by Lena Moses Schmitt