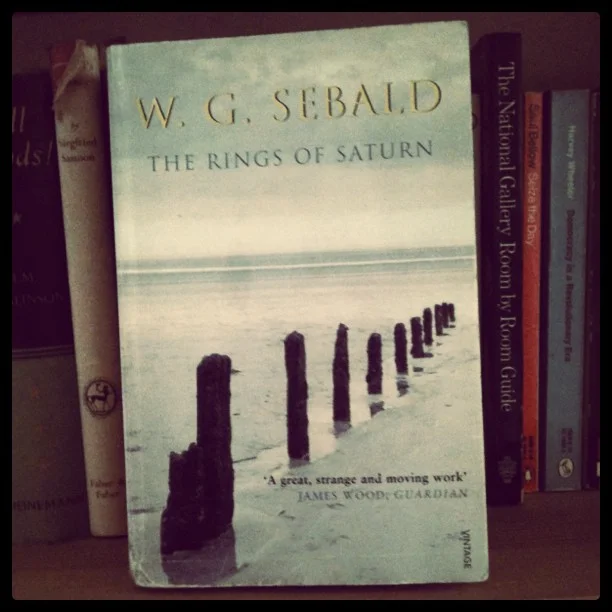

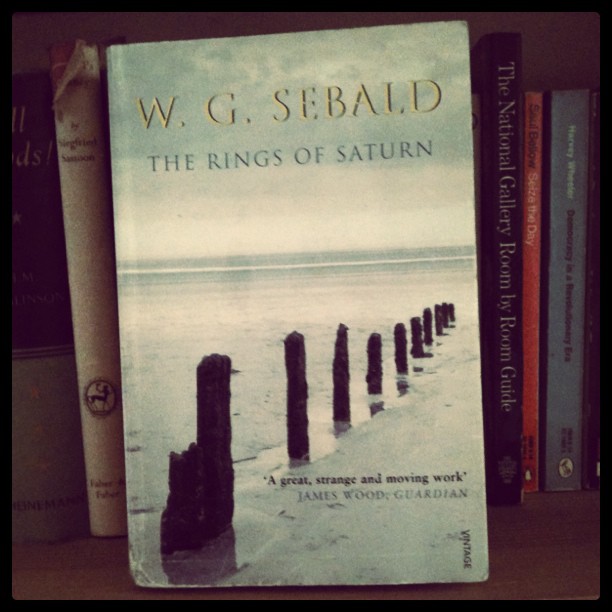

Reading Lately: Gabriel Blackwell on W.G. Sebald's The Rings of Saturn

I'm rereading W. G. Sebald's The Rings of Saturn right now, though I'm also reading a half-dozen other books, to wit, Rikki Ducornet's Brightfellow, Amber Sparks's The Unfinished World and Other Stories, Thomas Ligotti's Songs of a Dead Dreamer/Grimscribe, Chris Kraus's I Love Dick, David Rice's A Room in Dodge City, and Eric G. Wilson's The Melancholy Android. I think reading-wise, at the moment, things seem a little more scattered than usual, perhaps only because it takes me so much longer to finish books now (I took a new, somewhat more taxing teaching position last fall), and so as a result there are several books in that list I've been trying to finish for months. Thinking about such books is mildly disturbing, perhaps because picking up a book you've started weeks or months earlier with the intent to now, finally, finish it, is, in a way, like fulfilling too late an obligation you'd made only to yourself. But I began rereading The Rings of Saturn last weekend because the experience of reading Sebald, I remembered, is somehow very quiet, and I feel a need for quiet just now; at this point in the academic year, I feel as though I am in the middle of three dozen different conversations at all times. In The Rings of Saturn, Sebald walks. The reader walks. I do not mean the book is slow, but that, meanwhile, in life, I have places to be. I'm driven everywhere. (My wife, you see, is very kind.) Sometimes, reluctantly, I drive. Sebald writes, "After all, every foot traveler incurs the suspicion of the locals, especially nowadays," and so, perhaps in an effort to live up to the suspicion I feel I must sometimes incur in others, this suspicion I bring with me everywhere I go (or is it only that I imagine it?), I want to walk, to be a foot traveler, to in some way earn this strange inheritance. Perhaps, then, the rereading was in fact inspired by the to-me extraordinary experience of walking, alone or almost so, from one end of our enormous campus—it is the largest in the University of Florida system—to the other, two or three weeks ago. I met only one other person on that walk, a student who looked out of place, even though we were, at the time, quite close to the Commons. I remember he saw me and immediately veered off on a side path, as though he, too, were seeking solitude, or as though he'd seen something suspicious in me. The sky was darkening, after all, and it was windy out, and about to rain. Maybe it says something about me that my most vivid memories of the schools with which I've been associated come from moments when those institutions were not in session and yet I found myself on campus. In those moments, it is as though one has been plucked up from one's ordinary life and set down in a kind of terrarium or habitat, a zoo-like enclosure. (Is this the attraction of the so-called "post-apocalyptic"? That it is, at its heart, pastoral, but not, for all that, natural? I've put this thought in parentheses because I suspect it is neither original nor especially interesting—still, it is here.) There is a feeling of potential in such spaces at such times. One has the leisure of recalling the meetings one has had there without the danger of having those recollections interrupted, and, daydreaming, one imagines one has come to new understandings through those uninterrupted recollections. Though I think enough has been written about Sebald elsewhere, I can say that, until I'd begun rereading The Rings of Saturn, I'd failed to remember Sebald is quite capable, like his contemporaries Bernhard and Handke, of writing long, seemingly formless paragraphs that nonetheless have a kind of shadow structure, some quality that resists objectivity but is ultimately revealed in its effect on the reader. I think I admire such paragraphs because they inspire in me the kind of undistracted/distracted temperament that walking can, at least when I am only walking, that is, not simply moving from one item on the agenda to the next. I sometimes worry that, in contrast, my own writing—and perhaps this is true only for me—seems like the symptom of some nervous disorder. I have been, in this rereading, particularly impressed with how Sebald ends such paragraphs, typically with some sort of objective correlative, but also sometimes with an aside or even an ellipsis. Seldom does it seem abrupt.

...

Gabriel Blackwell is the author of Madeleine E (Outpost19, June). His most recent book is The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised-Men. He is the co-editor of The Collagist.