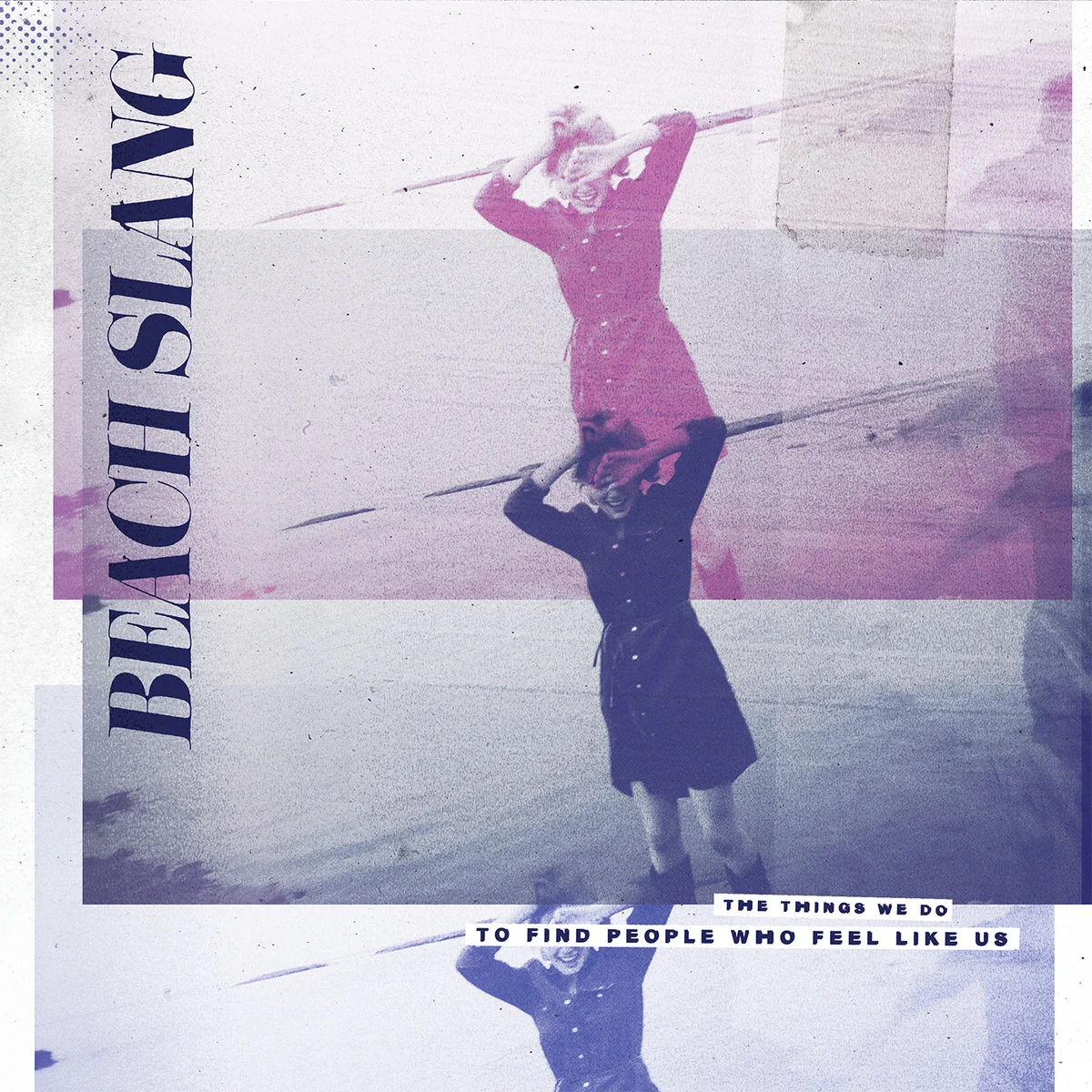

Greg Shemkovitz and James Brubaker on Beach Slang’s The Things We Do To Find People Like Us, Broken Glasses, and Growing Up Outsiders

Shemkovitz: In my teens and twenties, my relationship with music followed two paths. One path involved a lot of time spent moving from one car to the next as a lot boy at a car dealership, settling for the first available radio station, or later, as a letter carrier in a postal truck that had no cassette or CD player, enduring endless Van Halen on the classic rock station, Goo Goo Dolls on the alternative rock station, or Rush and Tragically Hip on a station that came in from Toronto, with the tag line, “H-T-Zed, we’re in your head!” This music became a murmur in the background of my workday, just to get me by until I could follow the other path. That is, in the evenings, friends and I would drive around the dark, snowy streets of Buffalo, chanting to bands like Snapcase, Shelter, Lifetime, and Weston. We packed ourselves into an old theater-turned-concert venue, shouting against the fuzz of guitars and the snap of the snare drum. We felt this music, celebrated life through it. I think Beach Slang represents the confluence of those paths. I came to them through Cheap Girls, who was touring with them around the time Who Would Ever Want Anything So Broken? was released. But instead of feeling the guitar through a half-stack on stage or cranking their songs in my car, I’ve been listening to them—and most music these days—through the tinny speakers on my computer while I write or grade student papers. So, with their full-length album, The Things We Do To Find People Like Us, which feels like an endless anthem, I wonder if I’m missing out on something. Should I crank this album through the stereo receiver, sleeping children be damned? Is this album meant to take me back to those days driving aimlessly with my friends? What is your experience with this album? Do we need to shout Snyder’s lyrics back at him with our chests pressed against the stage? Or can an old fool like me—though I’m younger than Snyder—appreciate this music within the confines of parental and professional responsibility (which I like to call feigned maturity)?

Brubaker: Yes, Greg—crank this album. Play it loud. Revel in this album. There’s no need to wake the kids, but the next time you’re in the car and don’t have to worry about damaging those tiny, still-growing ear drums, you owe it to yourself to turn this thing up—maybe roll down the windows if it’s not too cold—and let this album take you over. On my initial listens to The Things We Do to People Who Feel Like Us, I, too, listened on tinny speakers in my campus office. I listened almost academically, thinking of The Replacements, and The Hold Steady, and Japandroids. And, as I was listening with the volume low, enjoying the album enough, but not feeling particularly moved by it, I remembered the first time I put on Japandroid’s Post-Nothing in my car around the time of its release. I was a few months out from turning thirty, living in Oklahoma still and, since I was listening to a leak I’d pulled off of a message board after hearing good buzz about that album, spring was just hitting. I was headed to campus early to get some extra grading done. Within the first minute of “The Boys are Leaving Town,” my driver-side window was down. As soon as the opening riff of “Young Hearts Spark Fire” landed, I cranked the stereo and decided I wasn’t going to get that extra grading done—I was going to drive around, instead. And so I drove around Stillwater, Oklahoma in early spring, with my window down, letting Japandroid’s ecstatic rock music wash over me, delivering me from the life I was living and everything about growing up and getting older that I still hadn’t—and probably still haven’t—figured out.

But back to a few months ago, to my office in Missouri, as fall wore on, littered with days that felt more like summer—I realized that I needed to listen to Beach Slang loud. So I went for a drive and it felt good. In that moment, the experience of listening to The Things We Do to People Who Feel Like Us felt like the spiritual successor to my first listen to Post-Nothing—these were albums about getting older and navigating the alienation and various (dis)connections that many feel with age. Here’s the thing—I don’t know that I feel the things that Snyder feels. As much as I love this album and its gritty, grown-up punk ethos, I find that the closer I listen, the less I identify with Snyder’s songs. I love their energy and urgency, the crushing walls of guitars and Snyder’s ragged voice struggling to be heard—if Snyder growled nonsense like some sort of punk rock update of early Michael Stipe, I think I’d feel this album more deeply, would bask in the tension between getting older and trying to maintain that energy and urgency. But that’s only a piece of Snyder’s project here. What am I talking about, exactly? I’m not completely sure, yet, but I think it starts here, with a lyric from “Ride the Wild Haze,” in which Snyder sings, “”Let’s get fucking wild/Holy and strange/Let’s make the loudest sounds until we feel something.” There’s something in Snyder’s alienation that I struggle with when I begin to read his lyrics on the page—and maybe this is where my own age enters into the conversation—and I’m curious as to your thoughts on this, Greg—but as I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to feel more, and more deeply than I ever thought possible. Snyder’s lyric, above, speaks to a numbness that, quite frankly, I sometimes wish I could experience from time to time just to take a break.

And this idea is further complicated when we look at a song like “Too Late to Die Young,” which almost seems to pine nostalgically for a time when it’s speaker was younger and tougher, as if the only way he can cope with the present is to retreat to some romanticized notion of what it meant to be young (“The punks are wired/and these records feel tough…it’s always been enough” and “Baby turn your heart up” and “There’s honesty/in the neon lights/We’re animals/Drunk and alive). So, in answer to your question about whether or not we need to shout these lyrics back at Snyder—I think the answer, for me, is no. But I want to qualify that with a probably; I’m not sure that I hear much of my present in these lyrics, and end up imagining what my life would be like now if I was trying too hard to revisit my punk days. Still, all that said, just because I don’t necessarily identify with Snyder’s obsession with youth, doesn’t mean I don’t find the characters that populate his songs endlessly fascinating, for both their raw exuberance, and the low key tragic nature of the tension they feel between youth and maturity.

Shemkovitz: You bring up an interesting thought about feeling and numbness. There is so much more energy and sincerity and nostalgia in this album than in most music I’ve listened to in a long while. So, even when Snyder, as you put it, speaks to the numbness, he’s still doing it with such earnest feeling that I cannot help but be moved. I also thinks it’s interesting that you yearn for that numbness. I would have said that he’s looking back on a time when we felt everything more purely than we do now. There is so much fucking irony and snark today, I wonder sometimes if I’m allowed to feel anything the way I did when I was younger and chemically imbalanced. I guess that’s the feeling I takeaway from this album, especially if I don’t focus too intently on the lyrics. Like you, I don’t hear my youth in Snyder’s words but I hear something I may have wanted at one time.

Now that I’m reflecting on it, I can’t tell whether I’m numb or overwhelmed with feeling. When it comes to being a father and a husband and a teacher, I can say that I’ve certainly never felt more than I do now. But day-to-day worries and responsibilities really dull the edges. There are no extremes, just depth. Maybe what I’m saying—and this gets back to whether or not we should shout to the music and throw our fists in the air—is that it seems like the older we get, the deeper we feel but the less we’re able to show it. It’s less physical. And Snyder is telling us this in songs like “Young & Alive,” with lines like “Go punch the air with things you write” and “Go barely care with all your might.” Apparently when we were young (and alive), we were able to not care so intensely that we did so with our entire being. I don’t know if I’ve done anything lately with my entire being, let alone with undivided attention. Then there’s the hard-driving energy of “Young & Alive” that makes me feel like I can run through a brick wall. And here I am doing no more than drumming my fingers, tapping a pencil.

So, where I was probably just yearning before, now that I’m thinking about it, this album makes me hopeful. I want my kids to feel fully and without tether. They need to hurt and to love. They need to cry and scream and shout and laugh, and not because there’s a crowd or because it will end up on Youtube but because they are young and all-in and down for whatever. Snyder’s lyrics are for folks like us who can’t be that way anymore (which is sad) or maybe simply won’t (which is sadder). And maybe that’s the best part about this album. It’s for us. It complicates our emotions.

I can’t help but think of my high school days. This one time I was in my friend’s pickup truck (actually it was his father’s truck). We were cruising around town and jamming to something heavy like Earth Crisis or Lockjaw. Because I wasn’t driving, I was able to writhe more freely like an idiot, as I shouted into an invisible microphone. Oh, it was intense, I tell you. At some point in my thrashing, my glasses flew off my face and out the open window. We doubled back only to find them crushed on the street. If that happened today, I’d curse my stupidity and wonder how I might explain it to my wife. But back then I laughed my ass off. I probably didn’t even replace those glasses for a week. Rebel, I know.

Just thinking about that fills me with equal parts happiness and sadness. I think that’s exactly the sort of feeling Snyder wants us to have with this album.

Brubaker: That’s…really beautiful. The story about the glasses. And maybe a little uncanny. When I was an undergraduate, sometime in 2000, it must have been, I was standing outside of my apartment, smoking a cigarette with some friends. We were blasting Andrew W.K. loud enough that we could hear it out the front door. Now, imagine: I lived in a second story apartment and we were on the wood landing at the top of the stairs that led up to my door. In the process of rocking out to “Don’t Stop Living in the Red,” my glasses flew off my face and fell all the way down where they broke on the concrete. And I didn’t give a shit because, like you said, I was down for whatever. In fact, your take on this album has me sliding back towards my initial, pre-reading-the-lyrics position on it. And, as you pointed out some lyrics from “Young and Alive,” I’m now stuck on two lines from the same. The first: “Go scare your skull. Bring it to life.” And the second: “We are awake with hearts to riot.” Something in those lines seems to counteract some of the disaffected belief that the only way to feel anything is through booze and rock and roll. And maybe that’s what felt off, before—that’s what I was misreading. It’s not that the characters in Snyder’s songs don’t feel anything, it’s that they don’t know how to embrace those feelings, it’s that sometimes they need to do something to remember their mortality and their basic humanity so that they can even begin to process the heavy shit around them.

So maybe there really is beauty here, and maybe we’re just as awake as we’ve always been, “with hearts to riot”—and I’m suddenly left thinking of old nights roaming around Bowling Green, Ohio with friends, breaking into the long closed Milliken Hotel while it was being gutted and turned into Graduate Student apartments, the way we sneaked up the old, central staircase and looked at the moon shining through the old, cracked skylights. Or the nights we climbed up fire escapes to the roofs and looked down on the drunk college kids staggering in and out of the bars but feeling somehow intensely beautiful and alive from our secret vantage point. Another night that comes to mind: Dayton, Ohio in 2003, we went down to the river, four or five of us, and made a picnic from small things we could afford at Dorothy Lane Market, and drew on the riverwalk with chalk until two police officers came and asked us to leave. We weren’t breaking curfew. Weren’t causing harm. We were celebrating whatever it was about our lives that seemed worth celebrating. And there’s definitely a lot of that in Snyder’s lyrics.

And maybe, too, Snyder’s words want to remind us of the beauty in the abject.

One of those nights some friends and I took to the downtown rooftops in Bowling Green, we watched two club kids making out on the side of a horrible bar called Uptown. They were going at it hard, in a truly kind of beautiful, fearless, but also gross-because-they-were-probably-Greek-kids kind of way, until the young woman abruptly squirmed out from her spot between the brick wall and her beau so that she could puke in a nearby trashcan. Here’s the thing—while she puked, her dude snuck away so that when she turned around she found herself alone. She stood there for a moment, and though my friends and I were outsiders to her world—we were on the rooftops, they were dancing to shitty music in a club and making out, presumably, with strangers because that’s what those kinds of college kids did—I suddenly felt that the girl was one of us, that in her abandonment, we weren’t that different. That she, too, was an outsider. And that’s when I realized something truly important: we’re all outsiders. And maybe that’s why Beach Slang is such a vital project—because even though Snyder is singing about aging as a punk, he recognizes the basic outsiderness that all of us feel. He shows us, in song, what he tells us on the album’s closing track, “Dirty Lights,” that “The dirtiest lights shine the most.” And maybe that’s also the big irony in “Bad Art and Weirdo Ideas,” when Snyder sings, “I’m always that kid, always out of place/I try to get found/I’ve never known how,” before asserting that “We are not alone. We are not mistakes/We’re allowed to be aloud”; by virtue of everyone being outside of the thing, we are all the same, we all belong, which I know sounds cheesy, or at least Dan Harmon-y, but it feels so profoundly hopeful—and profoundly true—that, yeah, let’s pump our fists and shout these lyrics back at Beach Slang. These lyrics deserve at least that much.

Shemkovitz: Broken Glasses Buddies! Only through their combined impaired vision could they finally see clearly.

I totally understand what you’re saying. Maybe your anecdotes help but I’ve been trying to put a visual to this album and I keep coming back to rooftop vignettes at night. It’s always with a small group of people, plenty of shaky cam, and silhouettes set against city lights. It’s a whole lot of living in the now but not in any certain way, maybe because that would make it less universal. With the exception of the meditative nostalgia of “Too Late to Die Young,” which brings to mind early morning city streets passing by a taxicab window, the rest of these songs have the nondescript energy of the masses. I tried to apply a snippet of any given tune to the earbudded dancing silhouettes of an Apple commercial—because what better example of individualist conformity—but, as you point out, this album taps the outsider in each of us. Its universal appeal is that it makes us feel like we were part of a community of something beyond the norm. Oh, the teenage struggle to be accepted without label.

I think this further reinforces my belief that this album is for us, not the youth. The characters in these songs are teenagers—or twenty-somethings meant to appeal to teenagers, if we look at pop music like young adult books where we listen or read about people slightly older than us. But in this case I think these songs benefit from, if not require, an understanding that we are all outsiders and thereby all the same, in a unique way, of course (You’re special. Don’t worry.). I’m not sure if the average socially active teenager is capable of understanding how similar we are to our peers, even in simple moments like when we all reach the same milestone at the same exact time while wearing the same maroon cap and gown. Or maybe we are capable of understanding such a concept but that it takes so damned long to figure it out that some of us don’t quite get it until our late twenties and after ironically appropriating every last scrap of cultural capital in an effort to figure out what sticks, only to realize that most of our peers are going or have already gone through that phase, and now that we have, it’s time to crank it up as we look back on that enormously influential period of our lives and just laugh and maybe cry but nevertheless feel that very thing we were unwilling to quietly suffer then.

...

James Brubaker is the Associate Editor of The Collapsar.

Greg Shemkovitz teaches writing and literature at Elon University in North Carolina. His fiction has appeared in Foundling Review, Gihon River Review, the Journal of Compressed Creative Arts, Prick of the Spindle, and elsewhere. His first novel, Lot Boy, was released by Sunny Outside Press in 2015.