Wiley Wiggins In Conversation With Brandon Hobson

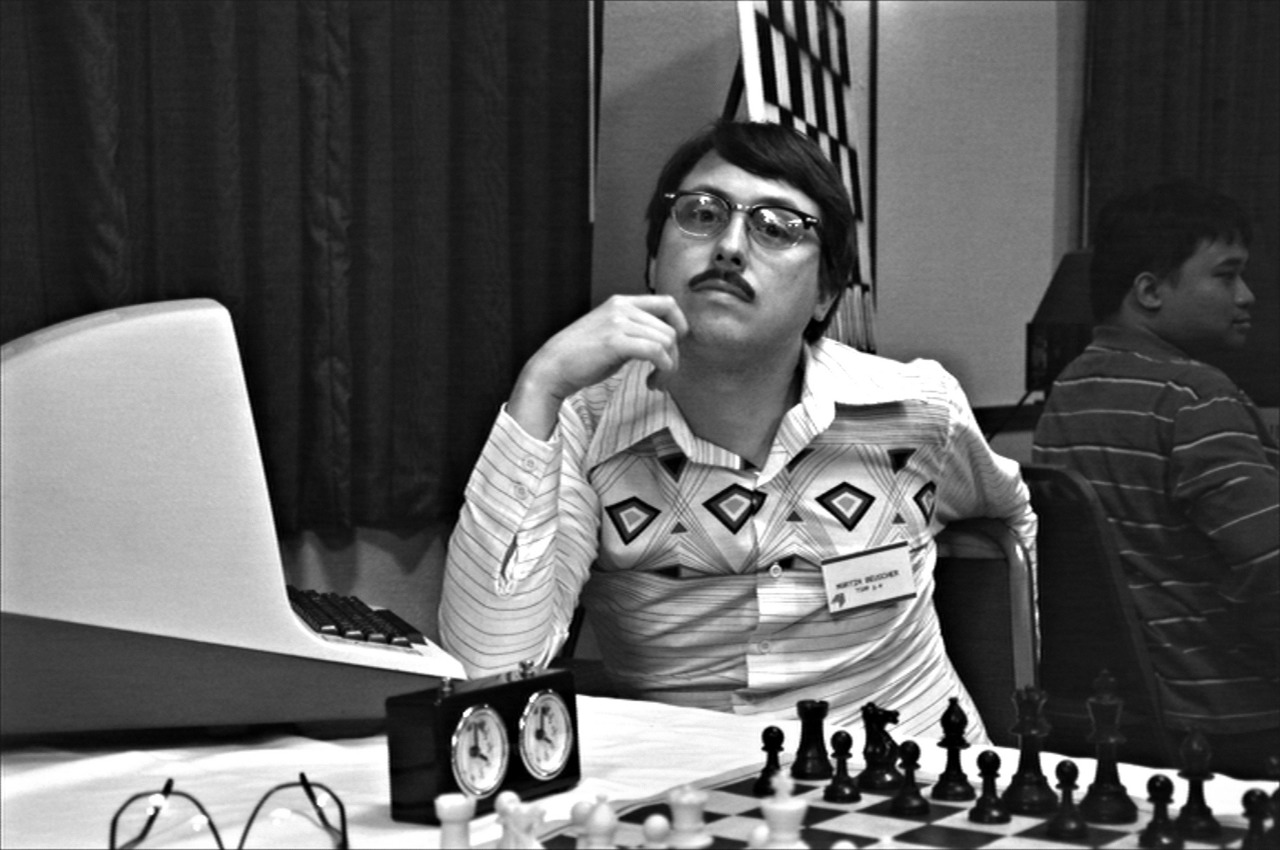

Wiley Wiggins is an American actor who appeared in such films as Dazed and Confused, Waking Life, and several independent films including Computer Chess. He currently is a co-organizer of an organization called Juegos Rancheros, located in Austin, Texas, where he lives. Juegos Rancheros showcases different independent videogames from around the world at a monthly meet up and at various cultural events such as film festivals. I had a chance to talk with Wiley recently. You can watch him chase cows and find more info about him at his website: www.wileywiggins.com – or follow him on Twitter @wileywiggins. —Brandon Hobson

Brandon Hobson: Do you still keep in touch with director Richard Linklater?

Wiley Wiggins: Yeah, I see him occasionally at Austin film functions.

BH: How did you first meet him? I know you were young. Did you audition for Dazed and Confused?

WW: I met him during the auditions. His co-producer met me outside a coffee shop, passing out fliers to kids to come audition. I was 15.

BH: What was he like?

WW: Good-natured. Rick was really protective and supportive of me as a kid, long after the movie was finished. We used to go on little trips to the local alternative bookstore together. I think he was worried that having been in a movie would alter my life for the worse. It was also nice that he brought me back for Waking Life. He has a great way of treating actors like collaborators, and I've tried to look for that quality in other directors I've worked for.

BH: Waking Life is fantastic. Did you contribute in any way to the animation?

WW: Yes, I animated a few shots in the movie as well as appearing in it. Bob Sabiston lives in Austin and is also part of the indie videogame scene here to a small degree.

BH: He did the animation for Waking Life?

WW: Bob was the animation director for Waking Life and also wrote the software that we used to animate it. He has an animation studio here called Flat Black Films that’s done a handful of other projects with the same animation style. He’s also released an animation program for the Nintendo 3DS called Inchworm Animation and a few small iOS apps and games.

BH: Do you keep in touch with anyone from Dazed and Confused or Waking Life?

WW: In the last five years or so I haven’t really kept in touch with people who don’t live in or visit Austin frequently. We had a 20 year reunion a couple of years ago and I saw a few folks there. Even Waking Life is over a decade old now which seems odd to me.

BH: Do you read much fiction or poetry?

WW: Not as much as I’d like to, lately. The last few novels I read were The Peripheral, The Goldfinch, and I re-read a book of Peter Carey short stories for something I’m working on. So mostly, popular novels read during air-travel.

BH: Are you playing a role from one of Carey's stories for a film, or working on a script based off of it? And what other future film projects are you working on?

WW: I'm adapting one of the stories in The Fat Man in History. Right now it's just a writing exercise. I haven't looked into the rights yet. I don't have any film projects in the works at the moment other than a few video art installations. Computer Chess was the last feature project I worked on.

BH: I thought you were really funny and great in Computer Chess. I enjoyed that film a lot.

WW: Thanks, it was a great experience working on that project.

BH: Did you have more freedom in that film? Is it one of your favorite roles you’ve played?

WW: I don’t know, I’m still very fond of Dazed and Confused, but it’s hard to have to see yourself as a 15 year old forever. I did feel like I had a lot of stake in Computer Chess, plus it’s the first time anybody has ever really let me play a grown-up.

BH: How well do you know the director, Andrew Bujalski? I taught my 8-year-old to play chess last year, so every once in a while we play. Do you play much?

WW: I’ve been good friends with Andrew since the 90’s, but we’d only really worked together once before (just as actors) in our friend Dia Sokol’s movie Sorry, Thanks. I’m a terrible chess player, but I am a vintage computer buff. I got to take part in picking the hardware and getting it running (or at least looking like it was running in some cases). We had some chess experts on hand, and every game you see in the movie was scripted out with play styles for the individual programs in mind. Board positions from 2001: A Space Odyssey’s HAL vs. Poole are visible in a few shots as well.

BH: What gaming projects are you currently working on?

WW: The big game I’ve been working on for a few years now is called Thunderbeam, It’s a sort of pastiche of “UFO” and “Space 1999” era sci-fi tropes, with an original score by The Octopus Project (an Austin band I’ve worked with a lot in the past). It’s been a great collaboration with a handful of really great visual artists and creative coders up to this point. Things are slowing down a little bit for various reasons (lack of money, people having babies, day jobs) but I’m hoping we’ll have something to show off very soon. In the meantime I’ve been toying with some smaller projects, like a loose game adaptation of Richard Brautigan’s hippy commune novel In Watermelon Sugar and an all-text multiplayer game that runs inside the chat client Slack.

BH: Did you play a lot of Infocom games as a kid? They were my favorite.

WW: I actually know the the modern version of the computer language that was used to write Infocom’s text adventures. I played a lot of Infocom games, A Mind Forever Voyaging, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Zork, and Wishbringer were a few faves. Now I have a hard time getting excited about games that use a text parser as input, because so much time is spent trying to guess what you can do. The parser says “hey there’s no visible controls here because you can do ANYTHING” but that’s really a lie because in any given context you can do like, ten things, and you don’t know what they are. I’m ok with guessing and obscured controls in a game, but the 'I DON’T KNOW WHAT “POOP” MEANS' parser errors ruin it. The joy of a videogame as opposed to say, a board game, is that you can’t do something “wrong”. You bounce off the walls of the world, there’s no illegal action. The idea I am kicking around for a multiplayer text game uses humans to fill in the gaps for what the computer can’t understand. It’s kind of a computer assisted role-playing game.

I was pretty mesmerized by some of the graphical games that came after text adventures, especially stuff like Deja Vú and Shadowgate on the original Macintosh. I love the look of the dithered black-and-white art in those versions. There was a French game for the Atari ST called Captain Blood that I was also very fascinated with. It had a vast, explorable (mostly empty) Galaxy with various alien inhabitants that spoke an alien language using scary, primitive speech synthesis. You had to decipher the language and manipulate these characters into helping you.

BH: We had a Commodore 64 and, before that, a Texas Instruments machine thing with a spine-tingling 16k of ram. My favorite Infocom games were Deadline, Zork, Witness, Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Infidel was hard.

WW: There’s still quite a bit of interactive fiction being written now by folks like Emily Short (Blood & Laurels, Bee) and Jim Munroe (Everybody Dies, Guilded Youth). I also really like the turn based aspect of those games, and that extends to graphical strategy games for me. My friend Adam Saltsman is working on an amazing and beautiful strategy game called Overland that is just dripping with style. I think he’s planning on releasing this year.

I’m pretty focused on games and interactive art now, but I also kind of feel like someone with a lot of creative energy who never really found their medium. I like acting but I feel like indie film is incredibly oversaturated, and I don’t necessarily feel like my physical presence is going to improve most movies. Maybe when I get old and craggy-looking. Right now I’m much more interested in building little virtual ships-in-bottles than I am in seeing my own face in stuff. Of course it’s great and a lot of fun when someone like Andrew calls me and says he has something for me to do in one of his projects.

BH: What’s your connection to the band the Octopus Project?

WW: I’ve worked on lots of projects with them, mostly as a video projection artist. A lot of what we do involves visuals that are generated live, and are manipulated by sound and other live inputs. I have played keys in a band before but I wouldn’t consider myself a musician. I’m definitely passionate about music though, and I like to be around folks who make it.

I mentioned the Inform7 earlier, the language used for writing interactive fiction. Give me a theme and I’ll try to make you a sample game.

BH: What about a theme of dead rock stars? Cobain, Joplin, Hendryx?

*Wiley sent me a link to a text adventure he quickly wrote called Roger’s House, based on Syd Barrett from Pink Floyd, which was fun to play.

BH: I love it—fantastic. As a kid one of the things I liked about text games is that whenever I played them I forgot they were programmed. I think this is one of the great things about them, that there's an exchanged of consciousness between you and the narrative, much like the way of reading fiction. In Computer Chess when your character types "Who are you?" etc. As a kid that's what I would type sometimes, questions like this.

WW: That scene in Computer Chess was definitely influenced by “Eliza”—a really primitive chatbot that was available for some early computers that acted like a psychoanalyst. Because it had a tendency to deflect your questions back at you, it managed to preserve the integrity of your perception of it as another person, rather than a program.

BH: Do you develop games full-time now?

WW: No, it's just a hobby right now. I'm really still learning a lot. I started a small game development company with my friend James after bonding over a handful of older games that had stuck with us into adulthood. We decided to try to make something that had the feel of a classic graphical adventure game but had less linear gameplay. Something that introduced new game design ideas. Hopefully it will be subversive enough to not come off as straight nostalgia. There have been really interesting new adventure games in the last few years, so we aren't the only ones thinking along these lines. Kentucky Route Zero, Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP, and Broken Age all brought new ideas to the table as far as the genre goes.

BH: What do you see as the future in gaming?

WW: I think a lot of things that currently fall under the overburdened descriptor ‘videogames’ will all get their own names and followers and syntax. I think you are going to see a lot of interesting things that are no longer constrained by screens and that we don't have names for yet, virtual architecture, brand new senses, things we can't imagine yet. The negative side of that is I think that as long as all these new media are controlled the way videogames were—commodified and marketed to strict, self-perpetuating demographic stereotypes, then they'll be destructive. My generation has spent an incredible amount of time eeking-out hidden meaning from commercial mass media in order to connect with the world as it is. It's not just that there's hidden value in lowbrow culture, (there will always be value as long as the occasional human is allowed to leave their fingerprints on the products they produce). It’s that there’s not really protected space that nurtures self-expression outside the ivory tower of academia or the vulture-picked garbage dump of social media. We ought to be able to create and experience interactive works without them needing to be "products" at all, but as a form of communication as natural and adaptive as the words we speak.

BH: By “virtual architecture,” do you mean more virtual reality type stuff?

WW: Yeah, a game can serve as a sort of place. VR definitely makes that more immediate, especially with new advances like total body position tracking. Also, it's surprisingly easy to build stuff for most of the consumer headsets that are getting ready to come to market. Last month one company released a tiny high-quality 360 degree camera that costs less than a smartphone. Standard 3D game tools like Unity have a fairly straightforward pipeline to VR, and those tools have free versions and huge and supportive user bases.

I’m also excited about experiments in form that don’t rely on fancy new technology though. Last night we were showing off tiny games made for an imaginary game console with constraints that mimic the original Nintendo entertainment system. I have kind of a wicked hang over right now because we show these games off in a bar with a bartender that loves to try to get me to do shots with her.

BH: Sorry about your hangover. What’s your favorite drink?

WW: This is just a cheap beer hangover, but I like scotch whisky if it isn’t too peaty. Glenmorangie nectar d'or is nice.

BH: I haven’t tried Glenmorangie nectar d’or, but maybe I can trick someone into buying it for me. I like Glenfiddich when I can afford it.

WW: Fancy scotch is definitely a sometimes food.

BH: I heartily agree.

...

Brandon Hobson is the author of Deep Ellum and Desolation of Avenues Untold. He is a 2016 recipient of a Pushcart Prize. His writing has appeared in The Believer, NOON, Conjunctions, The Paris Review Daily, Post Road, New York Tyrant, and elsewhere. You can read more here: http://brandonhobson.com