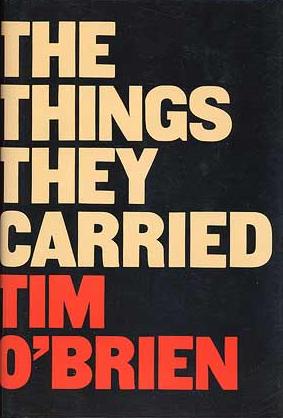

The book that I was reading when Nathan Knapp asked me to tell you what I was reading was Chelsea Girls by Eileen Myles, but that seems boring to talk about because just about everyone I know who likes books has either read it or is reading it or plans to read it soon. So let’s just say that I liked it. The reasons I liked it are very similar to the reasons why I liked the book I do want to talk about, which is the one I read a few books back: The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien. Both books are not stories, not memoirs, not novels, but somewhere hazy in between; both simultaneously reveal and conceal the author (which telling the capital-T Truth inherently does); both feel that they were written because the writer wanted/needed to tell those stories in particular, rather than writing them to make money or because they were trying to do what we are told stories are supposed to do.

I read The Things They Carried because I assigned it for class. I assigned it because a lot of the other books on that syllabus were very “female” (e.g. The Bell Jar, Their Eyes Were Watching God) and so I wanted something “male” to balance it out, and also because people are really into their guns around here (West Virginia) and so I figured they would appreciate a book about war. I’d also never read it before. (I’m not sure if you’re supposed to do this – assign books you’ve never read—but I do this kind of a lot and I enjoy doing it because it ups the ante or something.) I had read several of the stories, so I figured that was basically the same as reading the entire book, but then my husband told me no, it’s not the same at all, that book is amazing, one of his favorites, and I should read it.

The book that I was reading when Nathan Knapp asked me to tell you what I was reading was Chelsea Girls by Eileen Myles, but that seems boring to talk about because just about everyone I know who likes books has either read it or is reading it or plans to read it soon. So let’s just say that I liked it. The reasons I liked it are very similar to the reasons why I liked the book I do want to talk about, which is the one I read a few books back: The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien. Both books are not stories, not memoirs, not novels, but somewhere hazy in between; both simultaneously reveal and conceal the author (which telling the capital-T Truth inherently does); both feel that they were written because the writer wanted/needed to tell those stories in particular, rather than writing them to make money or because they were trying to do what we are told stories are supposed to do.

I read The Things They Carried because I assigned it for class. I assigned it because a lot of the other books on that syllabus were very “female” (e.g. The Bell Jar, Their Eyes Were Watching God) and so I wanted something “male” to balance it out, and also because people are really into their guns around here (West Virginia) and so I figured they would appreciate a book about war. I’d also never read it before. (I’m not sure if you’re supposed to do this – assign books you’ve never read—but I do this kind of a lot and I enjoy doing it because it ups the ante or something.) I had read several of the stories, so I figured that was basically the same as reading the entire book, but then my husband told me no, it’s not the same at all, that book is amazing, one of his favorites, and I should read it.

He was right. And I was right—my students loved this book. It does what I want all books to do: tells stories simply, using simple language. It read as though the stories inside it had to be told, as though they were tumbling around and around in Tim O’Brien’s mind and he wrote them down hoping it would finally get them out.

All writers use tricks, and this book, as simply as it reads, is full of them. But in O’Brien’s hands they don’t feel like tricks at all—more like transgressions that he allows us to be privy to. In “Notes,” O’Brien addresses the story that came before it, “Speaking of Courage.” He tells us what was true and what wasn’t. He tells us what led to him writing the story in the first place. By doing so, he implicates himself as a human being capable of ugliness and cowardice. “Speaking of Courage” is powerful, but it is also neat and careful, following the rules set down by any writing workshop. “Notes” blows that all up, and shows the messiness underneath. It shouldn’t work, but it does. It ends up being one of the most powerful pieces in the collection.

Other tricks O’Brien plays: He addresses you, the reader. He breaks the "fourth wall." A lot of things in the book are "meta." All of this was done in 1990, way before Ben Lerner or Karl Ove Knausgaard or Shelia Heti, or the “rise of autofiction.” As that essay admits, autofiction is far from new—but there is something to admire in a book that feels incredibly fresh 25 years after its original publication.

Coincidentally, we finished the book on Veteran’s Day. My class was solemn that day. The final story is about the first death in O’Brien’s life: a girl he loved who died of cancer when he was a boy. The final clause of the final sentence says, essentially, that it is Tim O’Brien, the grown-up, war veteran writer, who wrote this book to save the life of Timmy, the little, grief-stricken boy. The whole book is emotional, and that story in particular—multiple students admitted it made them cry—but that single clause just killed me. In the stories I write, my intended audience is myself as a teen. (Probably why I think this essay about writing to old men seems so idiotic.) I was miserable then, suicidal, felt like a freak, and the things I write are an attempt to let that teen girl know things will eventually be OK. The Things They Carried is a book about war, something I know almost nothing about and don’t even care that much for as a topic, but O’Brien is able to take his own unique experience and turn it universal. Writing preferences like simple language are merely that—preferences—but, as I told my class, turning the personal universal is the one definitive characteristic of truly great art. (Maybe.)

...

Juliet Escoria is the author of the story collection Black Cloud, which was published by both Civil Coping Mechanisms and Emily Books in 2014, and named a ‘best book’ by Dazed, The Fader, Salon, and more. Witch Hunt, a book of poetry, will be published by Lazy Fascist in 2016. She was born in Australia, raised in California, and currently lives in West Virginia.