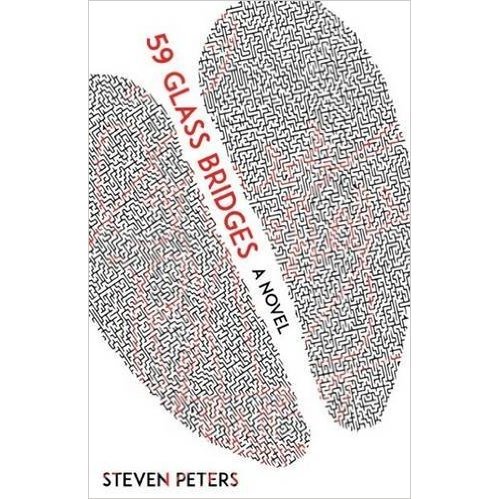

The unnamed narrator of Steven Peters’s 59 Glass Bridges (NeWest Press, 2017) drags the reader into a delightful maze, first stumbling around in calculating designs, and then when those don’t logically lead him to the exit, the narrator smashes through walls and climbs through the roof. He’s unraveled the one red glove he found on his person when he woke in the maze to use the thread as a sort of marker. But in this maze, the rules of physics don’t apply.

Or maybe they don’t exist: “I find myself at an intersection criss-crossed with red wool. My lifeline stretches down every corridor. I tug at the crossing threads and find them taut, but no matter how hard I yank it never pulls back on the thread ted to my finger.” It’s in this haunting space where we as readers navigate between the now and the back-then, riffling through the unnamed narrator’s memories as he traverses this seemingly impossible maze.

In the "now" sections, the narrator questions his experience, winding through the hows and whats and whys of this new landscape he’s found himself trapped within. Even his typical clothing—skinny jeans and chambray shirts in oranges, yellows, and reds—have been replaced by a mish-mash of “Salvation Army bin” selections, including a Stetson cowboy hat reminiscent of one he wore as a child. The narrator openly wonders: “Maybe I’m dead. Perhaps I’m in hell and hell is boring. Or purgatory—this place seems to fit the bill. No torture, but no paradise.” And, in this liminal space, with this untethered narrator as a protagonist, the reader is left wondering too.

We don’t know much about the narrator. But slowly, in the "back-then" sections, the narrator reveals himself through stories about his grandmother, other mazes, and the myths he grew up with. It’s the grandmother character who answers the narrator’s question, and who pushes us back into the now in an almost violent manner: “A little older, I asked my Grandmother if my myth was true. ‘I suppose it might be,’ she said, her voice breaking. ‘Now isn’t that sad?’"

This is the moment where the now and the back-then start to bleed together, revealing the underpinnings of the narrator’s psyche—and maybe the maze as well.

Told in 59 short chapters, Peters invokes Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities in an epigraph that frames the thematic and formal approach of the novel: “The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already there, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together.” When the narrator meets his guide for the maze, a ghostly teenage girl named Willow, the maze begins to develop the possibilities of this inferno.

Willow’s arrival is intriguing in the possibility she offers the narrative as a force to develop conflict in the maze. Yet, as a character Willow teeters on the precipice of being a Manic Pixie Dream Girl—that is, a female character whose only role is to enlighten the male narrator and convince him to embrace life. As Nathan Rabin suggests in his Salon essay “I’m Sorry For Coining the Phrase ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl,'” this stock character is an accessory to the main character’s development. As Willow is, after all, our narrator’s guide in the maze, she easily fits the Manic Pixie Dream Girl’s shoes. Yet as a reader, I keep hoping she’ll smash that boring mold wide open, in the same way that Peters has played with the landscape of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy.

At once irreverent and unflinchingly-honest in its examination of childhood and the pasts that make up who we are, 59 Glass Bridges is a blend of myth and memory. While the memories of a grandmother’s impact on the narrator’s life hold more tension than the journey through the maze itself, when these two narratives begin to mirror each other, warp, and twist, Peters’s novel is at its best.

...

Jenny Ferguson is Métis, an activist, a feminist, an auntie, and an accomplice with a PhD. She believes writing and teaching are political acts. Border Markers, her collection of linked flash fiction narratives, is available from NeWest Press. She lives in Haudenosaunee Territory, where she teaches at Hobart and William Smith Colleges.